The first thing I saw when I sat down at the Christmas table was the little American flag magnet on my refrigerator.

It was faded from years of sun through the kitchen window, holding up an old photo of my late wife smiling on a Fourth of July afternoon, a cheap paper flag in her hand and smoke from the grill curling behind her. Every time I looked at that magnet, I thought about service, about oaths, about the simple promise that you protect the people you love. That night, with my ribs taped and every breath feeling like it had splinters, I thought about it harder than ever.

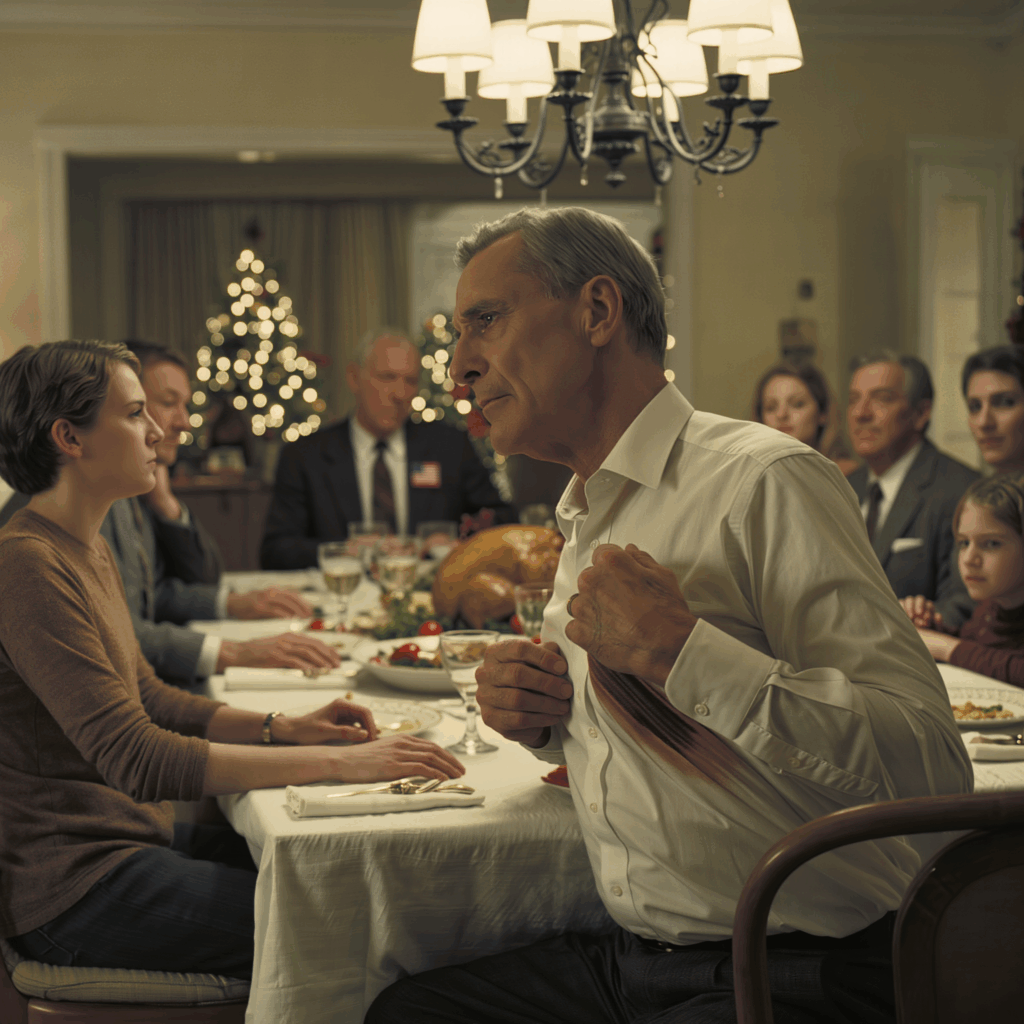

My daughter Emily sat on my left, knuckles white around her water glass. My younger brother Tom and his wife Linda were across from me, their Christmas sweaters suddenly feeling like costumes. Emily’s cousin Mark hovered near the end of the table, watching everything too closely. The turkey was carved, the mashed potatoes still steaming, Bing Crosby crooning faintly from the old speaker on the counter.

And then my son-in-law, Brandon, rose from his chair with his wineglass held high, that salesman’s smile stretched tight across his face.

“A toast to Marcus,” he announced, his voice just a little too loud for my small Minneapolis kitchen. “Still tough as nails, even after that terrible fall down the cabin stairs.”

There was a ripple of uncomfortable laughter. Emily flinched. Mark’s jaw clenched.

Brandon winked at me like we were sharing a private joke. “I guess the old man finally learned his lesson about wandering around in the dark.”

I felt the tape around my ribs under my shirt, each inhale a measured calculation between pain and pride. I pushed my chair back slowly, ignoring the protest from my body, and stood up. For a heartbeat, nobody moved. The only sound was the hum of the fridge and Bing crooning about a white Christmas.

I set my fork down with deliberate care, glanced once at that faded little flag magnet, then reached for the hem of my shirt.

“You’re right, Brandon,” I said, my voice steady. “Someone did learn their lesson.”

I lifted the fabric enough for everyone at the table to see the nightmare map of purple, yellow, and green bruises spread across my ribs and chest, the faint rope-like marks still ringing my throat. The room exhaled in unison.

“Just not me.”

Brandon’s face lost its color so fast it reminded me of crime-scene photos. His hand trembled, wine lapping at the rim of his glass.

If you want to know how we got to that table—how a retired cop with cracked ribs ended up teaching his own son-in-law a lesson about greed, fear, and exactly how far an old man can be pushed—you have to go back three weeks.

My name is Marcus Thornton. I’m sixty‑four years old, and before I retired I spent thirty‑six years in law enforcement, the last fifteen as a detective with the major crimes unit of the Minnesota State Police.

People like to think retirement is a soft landing. In their heads, it’s coffee that never gets cold, backyard grills with neighbors, golf games, grandkids crawling over your knees. For a while I believed that too. I pictured slow mornings with the Minneapolis paper, afternoons in the small garden my wife Margaret loved, maybe a fishing trip up north once in a while.

Life, of course, had other plans.

Margaret died two years ago in an oncology ward that smelled like bleach and stale coffee. Cancer doesn’t care how many years you’ve worn a badge or how many calls you’ve answered. She fought hard—harder than anyone I’d ever seen—but in the end, the disease didn’t blink.

After she was gone, the house got too quiet. The garden went a little wild. The coffee stayed hot because I stopped making full pots. Emily, our only child, became the anchor I didn’t know I needed.

Emily’s a nurse at St. Bartholomew Medical Center here in Minneapolis. She has her mother’s eyes, her mother’s stubborn streak, and this way of tilting her head when she’s listening that lets you know she’s really there with you. When she married Brandon five years ago, I tried my best to be happy for her.

On paper, he looked fine. Real estate developer, nice suits, big talk about “projects” and “returns” and “opportunities.” In reality, there was always something just a little too slick about him. A handshake that lasted a beat too long. A smile that never quite reached his eyes. He loved to brag about deals that hadn’t closed yet, money that wasn’t in the bank yet, plans built entirely on air.

But Emily loved him, so I shut up. That’s what fathers do. You swallow your doubts and hope you’re wrong.

In my thirty‑six years on the job, I’d worked every kind of case—homicides staged as accidents, domestic disputes that started with raised voices and ended with sirens, fraud schemes that wiped out people’s life savings. I’d learned one hard lesson over and over again: people are capable of terrible things when they feel cornered.

I just never imagined I’d see that lesson play out in my own family.

It was early December when my phone buzzed in my back pocket. I was in my workshop behind the house, trying to wrestle a crooked bookshelf into submission. Sawdust floated in the air, lit by the pale winter light coming through the small window. Classic rock played softly from an old radio I’d carried around since my academy days.

I wiped my hands on my jeans and checked the screen. Emily’s face filled it, bright and smiling.

“Hey, kiddo,” I answered, hitting the video icon. “You on break?”

“Kind of,” she said, tucking a strand of hair behind her ear. I could see the hospital hallway behind her, nurses moving like a fast-forwarded film. “Dad, how are you?”

“Good. Just trying not to lose a battle with a bookshelf. What’s up?”

She hesitated, just for a second. It was subtle enough that most people would have missed it. Thirty‑six years of interrogations had trained me to notice the moments people wished they could hide.

“Well,” she said, “Brandon and I were talking, and we realized you haven’t been up to the cabin since Mom passed.”

The word cabin hit me in the chest like a small, familiar punch.

Margaret and I had built that place almost twenty years earlier on a little stretch of shoreline up on Gull Lake, about ninety minutes north of the city. It wasn’t much—just a small A‑frame with a wraparound deck, creaky stairs down to a woodshed, and a dock that always needed a new board—but it had been ours. We’d stained the wood together, planted trees together, hammered nails while an American flag we hung from the deck railing snapped in the wind.

After Margaret died, I stopped going. Too many ghosts in that much quiet.

“I don’t know, Em,” I said. “It’s winter. Roads can get ugly, and that place isn’t really set up for cold-weather stays. The furnace is old. The plumbing’s a mess.”

She smiled, but it didn’t quite reach her eyes. “Brandon’s already thought of that. He had the heat turned on remotely, says he’s been driving up to check on the place. Everything’s ready. We just thought… it might be good for you. For all of us. A weekend away. Just the three of us. No phones, no distractions. We could make Mom’s beef stew, play cards, walk by the lake.”

Margaret’s beef stew. She’d made it every year on our anniversary, on the first snowfall, whenever life kicked us especially hard. Beef, potatoes, red wine, a bay leaf she insisted had to be broken in half for good luck. I could almost smell it as Emily spoke.

“Please, Dad,” Emily added softly. “You’ve been cooped up in that house too long.”

There it was—that thin, trembling note in her voice. Not quite desperation. Something close. Guilt, maybe. Or worry.

A sentence floated up from the back of my memory, from an old case file: When your gut whispers, listen before it starts to scream.

“Alright,” I said finally. “When were you thinking?”

“This weekend,” she said quickly, like she’d been braced for a no. “We drive up Friday afternoon, stay through Sunday. I’ll make Mom’s stew.”

That sealed it. I sighed, then smiled. “Okay, sweetheart. Count me in.”

Her whole face lit up. “Perfect. Brandon will pick you up Friday at two. I’ve got an early shift but I’ll follow you up as soon as I get off. Love you, Dad.”

“Love you too, Em.”

The call ended, but the unease remained, buzzing under my skin like a distant electrical current. Brandon offering to turn on the heat, driving up to check the place, suggesting cozy weekends—none of that sounded like the man who’d always complained the cabin was “too rustic, too far, no cell service, nothing to do.”

I told myself maybe he was trying. Maybe he was finally choosing family over the next big deal. Maybe grief had turned me into a suspicious old man who saw shadows in every corner.

But the thing about instincts is this: once they’ve saved your life a few times, you learn not to ignore them.

On Friday, the sky over Minneapolis was a flat sheet of gray, the kind that promised snow without the courtesy of saying when. I packed a small duffel—thermal shirts, wool socks, jeans, my blood pressure meds, a paperback I’d been pretending to read for six months. On my dresser, in a shallow wooden tray, lay my old leather badge case.

The badge itself was dull now, edges worn smooth from years of brushing against my hip. Stuck into the leather above it was a tiny enamel American flag pin Emily had given me the day I retired.

“For when you forget who you are without the uniform,” she’d told me, pinning it in place.

I picked up the case, thumbed the little flag, and slipped it into my pocket without quite knowing why.

At exactly two p.m., right on the dot like always, Brandon’s black Ford F‑150 rolled into my driveway. He prided himself on being “a punctual guy,” though I’d noticed he mainly reserved that punctuality for things that benefited him directly—meetings with investors, golf with clients, dinners where someone else picked up the check.

He climbed out of the truck with his usual swagger, wearing a designer coat that looked too thin for Minnesota winter and sunglasses despite the lack of sun.

“Marcus!” he called, spreading his arms as if we were old college buddies. “Ready for a guys’ weekend?”

I loaded my bag into the backseat and climbed into the passenger side. “Where’s Emily?” I asked, glancing at the empty back.

“Change of plans,” he said, pulling away from the curb a little faster than necessary. “She got called in for an emergency shift. Multi‑car wreck on the loop. She’ll drive up in the morning when she gets off.”

“Should we wait for her?” I asked.

“Nah,” he said quickly. “She insisted we go ahead. Didn’t want to ruin the weekend. You know how she is—always putting work first.”

There was a hard edge under the joke, like a dull knife under velvet.

We merged onto the freeway, headed north. Snowbanks lined the shoulders, gray with exhaust. The sky pressed down, low and heavy.

“How’s the real estate business?” I asked after a few miles of silence.

“Busy,” Brandon said. “Always busy. Got a couple of big developments in the works. Commercial properties, mixed use, you know how it is.”

“I don’t, actually,” I replied mildly. “I spent my life chasing people who lied about money instead of making it.”

He laughed, but it sounded forced. “Well, trust me, it’s booming.”

For a while, the only sound in the cab was the low murmur of country music on the radio and the whine of the heater. Brandon kept checking his mirrors more than the sparse traffic warranted, index finger tapping against the steering wheel, jaw tight.

“Actually, Marcus,” he said finally, “I wanted to talk to you about something.”

There it is, I thought. Here comes the real reason for the sudden family weekend.

“Shoot,” I said.

He cleared his throat, slipped into his sales voice. “I’m expanding the business. There’s this commercial property I’m looking at—great location, insane potential. Big investment, but the returns could be huge. I was wondering if you might be interested in partnering up. Using some of your retirement funds. It’s a sure thing.”

There it was. The ask.

“How much are we talking about?” I kept my voice neutral, the way I had in every interview room I’d ever sat in.

“Well, to get a respectable stake, probably around two hundred grand,” he said, eyes fixed on the road. “But like I said, we’re looking at thirty, maybe forty percent returns annually. Easy.”

Thirty to forty percent annually. I’d heard those numbers before—from Ponzi schemers, boiler-room hustlers, smiling men in expensive suits who left retirees with empty accounts and heavy shame.

“Those are big numbers,” I said finally.

“They’re real numbers,” he insisted. “I wouldn’t bring this to you if it wasn’t solid. Family first, right?”

Family. I thought about Emily’s face on my phone, the worry in her eyes when she asked me to come to the cabin. I thought about Margaret’s voice in my memory, always telling me, Don’t sign anything you haven’t read twice.

“Let me think about it,” I said.

Brandon’s knuckles whitened on the steering wheel. “Sure,” he said after a beat. “Take your time. Just… the window won’t stay open forever.”

The highway thinned into a two-lane road shouldered by dark pines. Snow dusted the branches like powdered sugar. As we turned onto the narrow county road that led to the lake, the trees closed in tighter, the sky dimming with the early winter sunset.

Brandon drove too fast for the conditions, tires hissing on patches of ice, the backend of the truck shimmying now and then.

“Easy,” I said calmly. “No need to rush. Cabin’s not going anywhere.”

He didn’t slow down.

By the time we reached the driveway, full dark had settled over the woods. The cabin emerged from the shadows like an old memory—A‑frame roof hunched under snow, deck railing sagging slightly where Margaret and I had once leaned side by side to watch fireworks reflected in the lake.

The nearest neighbor was a couple of miles away. The air out here had that particular stillness you only get when the nearest city is a distant glow and the snow absorbs every sound.

We killed the engine. The sudden silence rang in my ears.

“I’ll grab the bags,” Brandon said. “You go ahead and get the heat going. Fire in the cabin, hot cocoa, the whole Hallmark Christmas package.”

I stepped onto the porch. Cold slapped my face, hard and clean. My breath puffed white in front of me. Inside, the cabin was colder than the air outside, the kind of cold that lives in walls and floors.

I flipped on the lights. They flickered, then steadied with a low electrical hum. My breath still showed in the air. Whatever Brandon had claimed about preheating the place, the thermostat on the wall told a different story.

I cranked the heat, then moved to the stone fireplace. The wood bin beside it was empty.

“Brandon,” I called. “We’re out of wood. Need to run to the shed.”

“Yeah, I’ll get it in a minute,” he answered from the back bedroom. A door shut. I heard his voice, low and urgent, the cadence of someone talking quickly on a phone while they still had a bar or two of signal.

I shrugged into my coat and stepped back outside. The path to the woodshed ran along the back of the cabin, down a set of narrow wooden stairs from the deck. Margaret and I had built those stairs ourselves one sweltering summer, wood warping under the heat as we cursed and laughed our way through it.

Over the years, the Minnesota winters had chewed on them—splitting edges, softening boards. Margaret used to say we needed to replace them before they became a lawsuit waiting to happen.

She’d been right about most things.

I made my way carefully down, boots squeaking on packed snow. The woodshed squatted at the bottom of the stairs, roof half-buried. I filled my arms with split logs and turned back to the stairs.

That’s when I saw it.

The second step from the top, just below the level of the deck, looked normal at first glance—snow-dusted, weathered, the same gray-brown as the others. But as I shifted my weight to climb, a thin, sharp line caught my eye along the side of the tread.

I frowned, set the logs down, and brushed snow away with my gloved hand.

The board had been sawed almost all the way through.

The cut was clean, fresh, the wood pale where the saw teeth had bitten into it. Someone had left just enough intact that the step would hold light weight, but one good press—one full grown man coming up from the shed with his arms full and his mind elsewhere—and the board would give way.

The drop from that point was six, maybe seven feet onto hard‑packed, frozen ground. Land wrong, and you could snap an ankle, crack a skull, break a neck.

A hinge moment, my brain noted automatically. The kind you don’t realize is a hinge until you’re on the other side of it.

I brushed the step again. Fine sawdust clung to the snow, powdery and dry. It hadn’t had time to get wet, to darken. Whatever had been done here had been done recently.

Within hours.

My breath hitched—not from the cold this time.

I straightened slowly, every sense sharpening the way it used to in the moments before a door got kicked in or an arrest was made. The woods seemed to lean closer. Somewhere in the distance, a branch snapped like a rifle shot.

I carefully stepped over the compromised board, testing each other tread with my boot. When I reached the deck, I took one slow look back at the stairs, at that almost‑invisible cut hiding under a thin blanket of snow, and then went inside.

Brandon was in the kitchen, unloading groceries from a cooler onto the counter—cans of soup, a bag of flour, some steaks, a bottle of bourbon he probably thought would soften me up.

“Found a problem with the stairs,” I said lightly, watching his face. “Second step is rotten through. Almost put my foot straight through it. We’ll need to be careful.”

He didn’t miss a beat. “Yeah?” he said, glancing over his shoulder with what looked like genuine concern. “That’s dangerous. Good thing you spotted it. I’ll take a look tomorrow when it’s light. See if we can patch it up.”

It was a good performance. Better than most I’d seen across interrogation tables.

But there it was—that tiny tell at the corner of his left eye, a quick twitch he couldn’t quite control. The same one I’d spotted when he talked about “guaranteed returns.”

He was lying.

“Yeah,” I said slowly. “Good thing.”

That night I lay in the bedroom Margaret and I had shared, staring up at the knotty pine ceiling. The house creaked and settled around me. Old memories pressed in from every side—late-night card games, Margaret’s laughter echoing off the rafters, the way the morning light used to pool in that exact spot on the wall.

I should have felt comforted. Instead, my mind lined up the facts like photos on a case board.

Brandon, suddenly interested in the cabin he’d always dismissed.

The conveniently timed emergency shift that kept Emily in the city.

The pitch for two hundred thousand dollars with “guaranteed” sky‑high returns.

The lies about having the heat turned on.

The landline I hadn’t tested yet.

And that freshly sawed stair waiting for someone who wasn’t watching their step.

Patterns are what solve cases. They’re also what keep you up at three a.m.

The next morning, gray light seeped in around the curtains. My ribs ached faintly just from sleeping in a strange bed—that low, familiar stiffness that comes with age and old injuries. I swung my legs over the side, took a breath, and promised myself I was going to treat the day like any other investigation.

Document. Observe. Stay two moves ahead.

In the kitchen, Brandon was already up, humming to himself as he poured coffee. He was chipper, almost giddy, the way gamblers sometimes look when they’ve convinced themselves the next hand will fix everything.

“Morning, Marcus,” he said. “Sleep well?”

“Well enough,” I replied. “When’s Emily supposed to get here?”

He checked his phone. “She texted. Shift ran long. Says she won’t make it till late afternoon. I figured we could do some fishing to kill time. Ice should be thick enough by now.”

Ice fishing on Gull Lake in December with a man I was starting to suspect wanted me gone. The picture in my head was almost funny.

“Maybe later,” I said. “My hip’s barking. Think I’ll stay here, read my book for a bit.”

His smile tightened. “Come on, Marcus. Don’t be boring. Margaret wouldn’t want you sitting around like some old man.”

The mention of my late wife’s name in his mouth made something cold unfurl in my chest.

“I said maybe later,” I repeated, voice even.

After breakfast, he pulled on his coat, grabbing his keys from the counter.

“I’m gonna run into town for supplies,” he announced. “We’re low on a few things. Should only be an hour, hour and a half. You gonna be okay here alone?”

“I’ve been taking care of myself for sixty‑four years, Brandon,” I said. “I think I’ll manage.”

He smirked like he thought that was funny, then headed out. I waited at the window until I saw the taillights disappear down the tree‑lined road.

Then I went to work.

First stop was the landline. The phone sat on a small table near the front door, exactly where Margaret had insisted it should be. “If you fall,” she’d said, “I want you to be able to reach it from the floor.”

I lifted the receiver. Nothing. No dial tone, no static, no click.

I moved the small table aside and crouched down, every joint complaining. The wire snaked along the baseboard, disappearing behind a narrow console table. When I pulled it gently away from the wall, I saw it: the cable had been cut clean through, the two ends tucked neatly out of sight.

Not pulled, not chewed by mice. Cut.

My ribs twinged as I straightened. The cabin, once my sanctuary, felt suddenly smaller.

Next, I went to the guest bedroom where Brandon had dumped his bag. It sat on the bed, half-zipped. I stood in the doorway for a long moment, listening to the wind soughing around the eaves. Crossing that threshold from suspicion to proof always feels the same, whether you’re in a stranger’s apartment or your own cabin.

Then I stepped inside and unzipped the bag.

Clothes, cologne, a brand‑name shaving kit. Beneath a layer of neatly folded shirts, my fingers brushed cardboard. I lifted out a slim, worn folder.

Inside were papers. Lots of papers.

On top: a mortgage statement for a commercial property in downtown Minneapolis. The amount due made my stomach dip—one point two million dollars. Past due notices were stapled to the back, red ink shouting words like default and foreclosure.

Behind that, a stack of receipts—a depressing parade of cash advances from ATMs inside casinos, each one a hammer blow. Five thousand here, ten thousand there, three thousand on a Tuesday most people had spent at work. I shuffled through them, did a quick sum in my head out of habit.

Close to three hundred thousand dollars, all told.

Brandon wasn’t just in trouble. He was drowning in it.

At the bottom of the folder, something made my breath catch.

Life insurance paperwork.

My life insurance paperwork.

Margaret and I had taken out a policy years ago, back when Emily was little and I was still kicking doors for a living. Half a million dollars. Enough that if something happened to me, Margaret and Emily could keep the house, keep their lives, not end up one of the families I’d seen wiped out by tragedy.

After Margaret died, I’d changed the beneficiary to Emily. I remembered signing the form at the kitchen table, my badge case with its little flag pin sitting beside the paperwork like a silent witness.

According to the documents in that folder, the beneficiary had been changed again six months ago.

To Brandon.

The signature at the bottom of the form looked like mine at a glance. On closer inspection, some of the loops were wrong, the angle of the M just a little too sharp. Good enough for someone who didn’t know my handwriting, not good enough for someone who’d spent years examining forged checks and falsified statements.

The hinge of the whole ugly picture snapped into place.

Half a million dollars if I died.

Plus my house, my savings, whatever Emily would eventually inherit—all of it enough to plug the hole Brandon had blown in his expensive lifestyle.

I put everything back exactly as I’d found it, down to the angle of the folder in the bag. Then I stepped outside into the brittle daylight.

I walked the perimeter of the property, boots crunching on snow. At the woodshed, I saw fresh pry marks on the door where a lock had been forced. The snow on the handle wasn’t as deep as the drift around it.

Brandon had broken into the shed, taken a saw, and turned my stairs into a trap.

He hadn’t been planning on an accident.

He’d been planning on a body.

I pulled out my phone. Up near the road, you could sometimes scrape together enough bars to send a text. Down near the cabin, there was nothing but a mocking No Service in the corner of the screen.

I climbed cautiously up the stairs again, stepping around the sabotaged board like it was a live wire. At the top, I paused and took photos from every angle—wide shots of the stairs, close‑ups of the cut board, the fresh sawdust dotting the snow. Old habits die hard, especially the useful ones.

Back inside, I settled into the armchair by the fireplace with a paperback open on my lap and my phone within reach. I stared at the same page for a good twenty minutes without reading a single word.

When Brandon came back a little over an hour later, stomping snow off his boots and whistling tunelessly, I looked for the saw. It wasn’t in his hands. The woodshed door now sat obediently closed, snow brushed away.

He glanced at me, at my book, at the phone on the side table.

“Everything okay?” he asked.

“Quiet,” I said. “How was town?”

“Dead,” he replied. “Got what we needed, though.” He lifted a plastic bag in proof. “How about that fishing now? Ice is perfect.”

“Actually,” I said, letting just a little curiosity seep into my tone, “I was thinking about that investment opportunity you mentioned. Tell me more about it.”

His face lit up like a slot machine.

For the next forty‑five minutes, he paced around the living room like a motivational speaker, showing me pictures on his phone of glossy buildings and charts that looked like they’d been pulled from a stock-photo site. He talked about investors “lined up around the block,” about “projected returns” and “limited windows” and “once‑in‑a‑lifetime chances.”

He never once mentioned the foreclosure notices I’d seen.

When he finally ran out of buzzwords, he sank into the chair opposite mine, elbows on his knees, eyes intent.

“So,” he said. “What do you think?”

I closed the paperback, marking my place with a finger I wasn’t going to need.

“I think,” I said carefully, “that if I were going to put two hundred thousand dollars into something, I’d need to see quite a bit more. The actual property. Real financials. An attorney looking over the contracts. Maybe meet your partners.”

His jaw tightened. “There isn’t time for that, Marcus. I told you, this is moving fast. We’d lose the deal.”

“Then I guess it’s not meant to be.”

The temperature in the room dropped a few degrees. Outside, the wind shifted, rattling a loose shingle on the roof. Brandon stared at me for a long moment, his eyes going flat in a way I’d seen before—from men sitting on the wrong side of a metal table.

“You never liked me, did you?” he said quietly. “Never thought I was good enough for Emily.”

“This isn’t about—”

“Shut up, old man,” he snapped. “I’m talking.”

He stood, stepping closer. When he spoke again, his voice had that dangerous softness I’d heard minutes before punches were thrown in bar fights.

“You know what your problem is, Marcus? You think you’re so damn smart. So superior. With your war stories and your perfect little life. But you’re just a washed‑up has‑been who couldn’t even save his own wife.”

The words landed exactly where he wanted them to. Right in the small, unhealed place Margaret had left behind.

I kept my face still. “I think you should leave, Brandon.”

“Leave?” He laughed, sharp and humorless. “We’re in the middle of nowhere. It’s my truck. Emily won’t be here for hours. Besides, we haven’t finished talking about that money. I really need it. And one way or another”—his eyes slid to my duffel bag in the corner—“I’m going to get it.”

He took another step toward me. Thirty‑six years of training and muscle memory slid into place like a gun into a holster. I rose slowly, positioning myself so that the fireplace was behind me and he’d have to come through me to reach the front door.

“This is your last chance,” I said. “Walk out of here now, and we can talk about this tomorrow when Emily’s here.”

He smiled. It was the coldest expression I’d ever seen on a man I’d shared a Thanksgiving table with.

“Emily’s not coming,” he said. “I told her we needed some bonding time. Me and her old man. She thinks we’re up here drinking beer and playing cards.”

My hand drifted unconsciously to the outline of my badge case in my pocket, the little flag pin pressing against my palm.

“So what’s your plan?” I asked quietly. “I fall down the stairs? Slip on the ice? Heart gives out because I’m suddenly very far away from my medication?”

“My medication’s in my bag,” I added, nodding toward the duffel.

“Is it?” he asked, and his hand slipped into his pocket.

He pulled out a familiar orange pill bottle and tossed it gently in the air, catching it with insulting ease.

“Oops,” he said. “Must’ve fallen out. These old cabins are dangerous, Marcus. Lots of things can go wrong.”

Then he rushed me.

I’d seen younger, stronger men coming at me in alleys and living rooms and parking lots. The trick was never to meet force with force if you could help it. Use their momentum. Let gravity be your partner.

I stepped aside, pivoting just enough that his shoulder clipped mine instead of his weight driving me backward into the stone. He crashed into the coffee table, sending it skidding. A mug shattered against the hearth, coffee splattering like dark snow.

He recovered faster than I wanted him to. Desperation is a hell of a drug.

He came again, this time low. I tried to dodge, but sixty‑four‑year‑old muscles only move so fast. His fist connected with my side, a brutal, driving punch aimed right under my ribs.

Something snapped. White‑hot pain exploded through my chest.

I went down.

Brandon was on me in an instant, his knees pinning my arms, his hands wrapping around my throat. His fingers dug in, thumbs pressing hard against the sides of my windpipe.

The world narrowed to his face above me—flushed, eyes wild—and the roaring in my ears. Spots swam in my vision. My body, traitorous in its age, struggled to suck in air that wasn’t there.

This is how it ends, I thought distantly. Not in some alley on a call, not at a ripe old age in my own bed, but on the floor of my own cabin with my son‑in‑law squeezing the life out of me for half a million dollars.

Then another thought punched through the haze.

Margaret’s gun.

She’d insisted on keeping a .38 revolver up here, tucked in the drawer of the nightstand. “Black bears don’t care that you’re a cop,” she’d told me. “And neither do drunk hunters.” I’d rolled my eyes then, but I’d kept the gun loaded and oiled.

It was fifteen feet away. Down the hall. Around a corner.

Might as well have been on the moon.

Still, you learn things in thirty‑six years of grappling with people who don’t want to go to jail. Chief among them: as long as you can still move, you’re not out of the fight.

I bucked my hips violently, twisting to one side. The move caught him off guard. His weight shifted just enough that one of my arms came free. I drove my knee up as hard as I could between his legs.

He let out a strangled sound, collapsing sideways.

Air tore back into my lungs like broken glass. I rolled, gasping, vision tunneling in and out. Every breath sent knives into my ribs. The room tilted, steadied, tilted again.

Get up, I told myself. Move.

I crawled, dragged myself really, toward the bedroom. Behind me, I heard Brandon curse, furniture scraping as he fought his way upright.

“Marcus!” he snarled. “You’re just making this worse!”

I didn’t answer. I reached the bedroom doorframe, grabbed it to haul myself up, and stumbled to the nightstand. My fingers closed around cold steel.

The gun was where Margaret had left it, bless her stubborn soul.

I turned as Brandon lunged into the room. The .38 came up almost on its own, the way muscle memory drives you to hit your turn signal when you change lanes.

He skidded to a stop at the sight of the barrel, his hands flying up.

“Back off,” I wheezed, my voice shredded. “Now.”

“You’re not gonna shoot me,” he said, but some of the bravado had leaked out of him. “You’re a by‑the‑book guy. You’ve spent your whole life telling people they can’t take justice into their own hands. How are you gonna explain that to Emily?”

“Self‑defense,” I said. “And you’d be amazed what a man will do when someone decides his life is worth five hundred thousand dollars and some overdue bills.”

I motioned with the gun.

“Living room. Move. Slowly.”

He backed down the hall, hands still up, that slick mind of his clearly racing through contingencies. My ribs screamed with every step, but adrenaline papered over the worst of it.

“Sit in that chair,” I said when we reached the living room. “Hands on the armrests.”

I kept the gun on him while I dug into the junk drawer in the kitchen—a graveyard of old batteries, mismatched screws, and, thankfully, a half‑used roll of electrical tape.

The tape wasn’t ideal. Rope would have been better. Handcuffs best of all. But you improvise with what you’ve got.

I wrapped his wrists to the chair arms, pulling tight enough that the skin bulged around the black plastic. He winced but didn’t resist. I moved to his ankles, securing them to the legs of the chair.

“Too tight?” I asked when I was done.

He glared at me. “You can’t keep me here. Emily will come looking.”

“Landline’s dead,” I said. “No cell service unless you hike out to the road. The earliest Emily starts to worry is tomorrow. By then, the sheriff’s office will be here.”

His eyes flicked to my phone on the side table. “What did you do?” he asked slowly. “Before I got back from town.”

“I went up near the road,” I lied, letting the truth ride shotgun. “Got just enough signal to text Emily and my old partner. Told them I found some things that concerned me. That I might be in danger. That I needed help.”

It was a bluff, but a decent one. Brandon didn’t know that the only thing I’d done when he was gone was pace and take photos.

“You can’t prove anything,” he said, but the conviction had bled out of his voice.

I took out my phone, opened the photos app, and flipped the screen so he could see the images of the sawed stair, the fresh sawdust, the pry marks on the shed.

“Actually,” I said, “I can. Add that to the documents in your bag—the forged signature on my policy, the beneficiary change, the foreclosure notices—and what we’ve got is a pattern. You’d be amazed how much juries love patterns.”

His shoulders sagged. For the first time since I’d met him, he looked his age instead of the glossy, ageless salesman he tried to project.

“I didn’t mean for it to go this far,” he muttered. “The debts just… they kept coming. One bad hand turned into ten. I thought if I could just get access to some capital, I could fix it. I love Emily. I do. I was trying to save our future.”

“By taking mine,” I said.

“I needed that insurance money,” he whispered. “After you were gone, I was going to take care of Emily. I swear. The policy, your house, your savings… it would’ve covered everything and left plenty for her.”

“You would’ve bankrupted my daughter trying to pull yourself out of a hole you dug,” I said. “You don’t get points for bringing flowers to the funeral you arranged.”

He had no answer for that.

The house grew colder as the afternoon light faded. I kept the gun in my lap, my back pressed against a throw pillow Margaret had bought on clearance because she liked the color. The pain in my ribs settled into a deep, grinding throb. Every breath felt like someone tightening a belt around my chest one notch at a time.

“You know what the sad part is, Brandon?” I said eventually.

He stared at the far wall. “I’m dying to hear it.”

“If you’d been honest—if you’d come to me and said, ‘Marcus, I’m drowning here, I screwed up, I’m scared’—I might have helped. Not with your gambling, but with getting you into treatment. Helping you climb out. That’s what family does. They tell each other the truth and then they roll up their sleeves.”

“We’re not family,” he spit. “You made sure I knew that every day.”

Maybe there was a shard of truth there. Maybe I’d never given him the benefit of the doubt, never looked past the slick surface to see if there was anything worth saving underneath.

But it didn’t excuse what he’d tried to do.

We sat in a brittle silence as evening wrapped around the cabin. I didn’t dare leave him alone long enough to fetch more wood, so the fire shrank to glowing embers. Our breath started to show faintly in the air again.

Around nine p.m., headlights swept across the front windows.

For a second my heart kicked hard against its bruised cage.

Had my bluff worked?

The engine cut off. The front door opened without a knock.

“Dad?”

Emily stood in the doorway, snow in her hair, hospital badge still clipped to her coat, eyes widening as they took in the scene—me, battered and pale, gun loose but ready in my hand; Brandon taped to a chair, face waxy, eyes wild.

She went white.

“Dad,” she whispered. “What happened? What did you do?”

“Not what I did,” I said gently. “What he did.”

I told her everything. I laid it out the way I would have for a prosecutor—short, clear sentences, facts in order, no embellishment.

The sudden interest in the cabin.

The request for two hundred thousand dollars.

The cut phone line.

The sabotaged stair.

The forged paperwork. The attack. The missing medication.

As I spoke, I watched my daughter’s face transform. Confusion gave way to disbelief, disbelief to horror, horror to something harder—a kind of cold clarity I recognized from my own mirror after certain cases.

When I finished, the only sound in the room was the faint ticking of the old wall clock Margaret had found at a yard sale.

Emily turned to her husband.

“Is it true?” she asked.

Brandon swallowed. “Em, I can explain.”

“Is it true?” she repeated, the words clipped, precise.

He broke. “I was desperate,” he said. “I made mistakes. But I did it for us. For our future. You work so hard. I wanted to give you more. A better life.”

“You tried to take my father’s life,” she said, voice cracking. “How is that for us?”

She pulled her phone from her pocket.

“I’m calling 911.”

“Cell service is spotty here,” I reminded her quietly. “Landline’s been cut. You’ll have to drive toward town until you get bars.”

Emily looked at Brandon one more time, really looked. I saw something break and fall away in her gaze—illusion, maybe. Or hope.

Then she straightened, shoulders squaring.

“Let’s go, Dad,” she said. “We’ll take my car. He can stay here and think about what he’s done.”

“We can’t just leave him,” I said. Part of my brain still lived in policy manuals.

“Watch me,” she replied.

We left him there, taped to the chair in the dim cabin that had once been our refuge. Emily’s little sedan chewed through the snow‑dusted road, headlights carving a tunnel through the dark. After about twenty minutes, the No Service on her phone blinked away. Two bars flickered to life.

She pulled onto the shoulder, hands shaking as she dialed. The 911 operator’s calm voice grounded us both.

We drove straight to the county sheriff’s substation. My old partner, now Detective James Rhymer with the violent crimes unit, met us in the lobby, his face tightening when he saw the bruises blooming across my throat and the way I was holding my side.

“Jesus, Marcus,” he muttered. “You look like you’ve been through a wood chipper.”

“Feels worse,” I said.

We went into an interview room that looked just like the ones I’d interviewed people in for three decades, only older. I gave my statement. Emily gave hers. I handed over my phone with the photos of the stairs and the shed and the forged paperwork. I told James exactly where to find the folder in Brandon’s bag.

Deputies reached the cabin about three hours later. they found Brandon right where we’d left him, tape marks on his wrists and ankles, the cut landline wire hanging behind the console table, the sabotaged stair waiting outside like an open mouth.

They arrested him on the spot.

Attempted murder. Fraud. Forgery. Assault causing serious bodily injury.

The evidence, as we used to say, was overwhelming.

The ER doctor at St. Bartholomew confirmed what my body had been yelling since the moment Brandon’s fist landed—three cracked ribs, severe bruising, soft tissue damage in my throat from his hands. They wrapped my chest in what felt like half a roll of tape, gave me pain meds, and told me not to lift anything heavier than a gallon of milk for weeks.

Apparently, they hadn’t seen my turkey.

The story hit local news within twenty‑four hours. “Retired State Police Detective Survives Alleged Attack at Family Cabin,” the anchors said while my retirement photo flashed on screen—me in uniform, eyes a little less tired, badge shining under the harsh camera lights.

Neighbors left casseroles on my porch like it was a funeral. The guy who ran the coffee shop on the corner slipped an extra donut into my bag “by accident” every morning. People I barely knew stopped me on the street to say things like, “Heard what happened. Glad you’re okay,” and “That son‑in‑law of yours, what a piece of work.”

Emily had it worse.

The nurses’ station at St. Bartholomew buzzed with whispers. Patients’ families recognized her from the news, from the courtroom sketches that started appearing once arraignment made the papers. Some people hugged her. Some just stared.

She kept going to work.

“I can’t stop,” she said one night as we sat in my living room, the little flag magnet on the fridge catching the light from the TV. “If I stop, I’ll think about all of it, and then I’ll never move again.”

Three weeks later, I insisted on hosting Christmas.

“Dad, you don’t have to do this,” Emily protested. “You’re still healing. We can do something small. Just the two of us.”

“Family dinner,” I said firmly. “Normal food. Bad jokes. Too many leftovers. You deserve that much.”

Brandon, somehow, was out on bond while he waited for trial. His attorney had convinced a judge he wasn’t a flight risk, that he had strong ties to the community, that he’d “pledge to abide by all conditions.”

The fact that he’d tried to turn a weekend at the lake into an accident report apparently hadn’t weighed enough to keep him behind bars.

I was furious when Emily told me he’d asked to come to Christmas dinner.

“For closure,” she said quietly. “I need to look him in the eye one more time. With everyone there. I need to see who he really is.”

I’d seen who he was. I’d felt his grip tighten around my throat. I’d heard him pick apart my life with a few well‑chosen barbs.

But she was my daughter, and she was hurting in a way even thirty‑six years on the job hadn’t prepared me for. So I agreed.

Which brought us back to my small kitchen, to the turkey and the mashed potatoes and Bing Crosby and that toast.

“So, Marcus,” Brandon said, his voice carrying that practiced joviality he used in boardrooms and open houses. “Now that you’ve had time to think about things, maybe realized this was all just a big misunderstanding, when are you going to drop those charges? I mean, come on. We’re family, right?”

The table went dead silent. You could’ve heard a fork hit the floor from three rooms away.

I picked up my water glass, took a careful sip while my ribs protested, and set it down with deliberate care. Every eye around the table was on me.

“A misunderstanding,” I repeated. “Is that what we’re calling it now?”

“Dad—” Emily started, but I held up a hand.

“No, sweetheart,” I said, eyes never leaving Brandon’s. “Let me say this.”

I leaned back enough to see that faded little flag magnet on the fridge out of the corner of my eye and felt the familiar weight of my badge case in my pocket.

“You sabotaged the cabin stairs,” I began. “You cut the landline so I couldn’t call for help. You forged my signature on a form that changed the beneficiary of my life insurance policy from my daughter to you. When that didn’t work fast enough, you took my medication, you drove me to the ground, and you wrapped your hands around my throat until I saw black.”

Brandon’s smile cracked at the edges.

“You can’t prove—”

“The sheriff’s office has the photos,” I said calmly. “The saw marks, the pry marks, the cut wire. They have the documents from your bag. Your fingerprints on the saw they pulled from the woodshed. And I have these.”

I stood slowly, wincing as pain lanced through my side, and lifted my shirt just enough for everyone to see.

The bruises had shifted colors, but they were still spectacular—dark purples fading to sickly yellows, greens pooling along the edges. The faint rope‑like impressions around my throat looked like an ugly necklace.

“Three cracked ribs,” I said. “Severe bruising. Damage to the soft tissue in my neck. All documented in the ER the night you tried to turn me into a cautionary tale.”

I dropped the hem of my shirt and met his eyes.

“You didn’t teach me a lesson, Brandon. You didn’t prove I was old or weak or in your way. You proved something else entirely.”

He swallowed. “What’s that?”

“That you’re a coward,” I said quietly. “A coward who tried to take out an unarmed sixty‑four‑year‑old man for five hundred thousand bucks and still couldn’t get the job done.”

The silence that followed was louder than any shouting match.

Emily’s eyes filled. Mark’s hands flexed on the table like he was fighting the urge to jump across it. Tom just shook his head slowly, disappointment etched deep.

Brandon shoved his chair back so hard it scraped a harsh line across the tile.

“This is—” he sputtered. “I don’t have to sit here and be attacked like this. Emily, we’re leaving.”

“No,” Emily said.

He blinked. “What?”

She turned to face him fully, her voice shaking but her words steady.

“No, Brandon. You’re leaving. Alone.”

“That’s not funny,” he said, a nervous laugh bubbling up. “Come on, Em, we just need to get away from this toxic environment—”

“The divorce papers will be served tomorrow,” she cut in. “My attorney says with the criminal charges, I’ll get everything. The house. The car. Whatever’s left in the accounts. You’re going to prison, and when you get out, you’ll have nothing. No wife. No family. No future with me.”

“Emily, please,” he said, reaching for her hand.

She pulled it back like his touch burned.

“Get out of my father’s house,” she said. “Now.”

He looked around the table, searching for a lifeline, an ally, anyone who didn’t see him for exactly what he was. He found nothing but anger and pity.

“You’re all going to regret this,” he hissed finally. “I’ll appeal. I’ll fight this. I—”

“You’ll go to prison,” I said. “The assistant district attorney says you’re looking at ten to fifteen years, easy. And in state prisons, guys who go after seniors don’t exactly win popularity contests.”

His eyes flashed with pure hatred. Then he grabbed his coat, stomped to the door, and was gone.

We listened to the sound of his car engine revving, the tires spinning on the icy driveway, then fading into the distance.

After a long moment, Tom lifted his glass.

“To Marcus,” he said. “Tough as nails. Still here.”

Emily wiped at her cheeks, gave me a trembling smile, and raised her water.

“To Dad,” she whispered. “I’m so sorry. I’m so, so sorry.”

“There’s nothing for you to be sorry about,” I told her. “You loved the wrong man. That’s not a crime. What you did tonight”—I nodded toward the door Brandon had stormed through—“that’s what matters.”

We finished dinner quietly. No one mentioned the table scraps Brandon had left, congealing on his plate like a metaphor.

After everyone went home, Emily stayed behind. We sat in the living room, the gas fireplace flickering soft light over the photos on the mantel. Margaret’s smile beamed out from every frame—holding baby Emily, standing on the cabin dock with a fishing pole, leaning into me on the day I retired, her hand resting on my badge.

“He really would’ve done it,” Emily said finally. “If you hadn’t fought back.”

“Yes,” I said. “He would’ve.”

“And you kept yourself alive with everything you learned all those years,” she said. “All those nights I complained that you worked too much or were too tired from a case… you were out there learning how to survive people like him. So you could survive him.”

I smiled despite the ache in my ribs.

“Your mom would’ve shot him as soon as he walked up the cabin steps,” I said. “She never liked him much either.”

Emily let out a startled laugh—the first real one I’d heard from her in weeks. It loosened something tight in my chest in a way no pain medication had managed.

We sat there until the fire burned low and the house fell into that familiar, comfortable quiet. Father and daughter. Two people who’d walked through the same fire from different directions and somehow made it out the other side.

Brandon’s trial is set for March. His attorney is already sniffing around for a plea deal, something that’ll shave a few years off in exchange for a guilty plea and a show of remorse. The assistant DA says we may not even have to take the stand. The physical evidence tells the story loudly enough.

I sold the cabin not long after that Christmas. Too many memories woven into those walls now, the good layered over with something darker. A young family bought it—a couple with twin boys and a dog that immediately peed on the porch. I watched them from my truck as they carried boxes inside, laughter puffing in the cold air.

The money from the sale went into a trust in Emily’s name. “For when you’re ready to build whatever comes next,” I told her.

My ribs healed slowly. At my age, everything does. There’s a permanent ache there now, a weather forecast built into my bones. Some mornings, it takes me a little longer to straighten up. Some nights, when I roll over in bed, the twinge reminds me of the cracking sound that filled the cabin three weeks before Christmas.

But I’m here.

Still breathing. Still standing.

Brandon thought turning sixty‑four meant I was done, that experience and stubbornness and a lifetime of seeing the worst in people added up to frailty.

He was wrong.

These days, once a week, I drive over to the community center and teach a self‑defense class for seniors. We don’t do anything fancy—no movie moves, no spinning kicks. We practice awareness. Boundaries. How to fall safely. How to break a grip. How to say no and mean it.

“Don’t ever let anyone convince you you’re helpless just because you have a few more candles on your cake,” I tell them. “Stay aware. Stay strong. Trust that little voice in your gut. It’s there to keep you alive.”

After class, I go home to my quiet house. I make myself dinner. Sometimes I pour a small bourbon and sit at the kitchen table where everything started, the old photo of Margaret and that faded American flag magnet still watching over the room.

Emily’s doing better. Therapy helps. So does work. So does time. She still apologizes more than I’d like.

“I should’ve seen it,” she says. “I ignored all the signs.”

“You didn’t do this,” I tell her every time. “Brandon did. He made those choices. He built that house of cards. You’re one of the people he almost hurt. That makes you a victim, not an accomplice.”

Sometimes, late at night, when the house is dark and the only sound is the hum of the refrigerator, I think about those seconds on the cabin floor. The spots dancing in my vision. The weight on my chest. The hands at my throat.

I think about how close I came to never seeing another sunrise, never feeling my granddaughter’s tiny hand curl around my finger someday, never hearing Emily laugh in my living room again.

And then I think about Margaret.

I can almost hear her voice, that no‑nonsense tone she used when I was spiraling in my head over a case.

You survived, Marcus. Now stop dwelling and start living.

So I’m trying.

One careful breath at a time.

The pain in my ribs has become a kind of metronome, ticking off the beats of my second chance. Every time it flares when I twist the wrong way or laugh too hard at one of Emily’s sarcastic jokes, it reminds me of that weekend. It reminds me of the stairs, the sawdust, the pill bottle in Brandon’s hand.

It reminds me of the lesson he tried to teach me—that I was weak, that I was expendable, that I was an obstacle between him and a half‑million‑dollar payoff.

And it reminds me of the lesson he actually learned instead.

Age isn’t weakness.

Experience isn’t irrelevance.

And a desperate man with a sloppy plan is no match for an old cop who still knows how to read a crime scene, how to follow a pattern, how to listen when his gut whispers, This is wrong.

Brandon will spend the next decade, maybe more, in a state prison. He’ll have a file that follows him forever, a name that pops up every time someone runs a background check. He’ll wake up every morning knowing that he tried to turn a man’s life into a number on a policy and failed.

That’s justice. Not the flashy TV kind with dramatic speeches and slammed gavels. The quiet, Midwestern kind. Slow. Thorough. Relentless.

As for me, I got something better than revenge.

I got my life.

I got my daughter.

I got to stand in my own kitchen at Christmas, ribs taped, hands shaking, and look a man in the eye as I told the truth out loud with my entire family listening.

Most nights, before I lock up, I take my old badge case out of my pocket and set it on the counter beneath that faded flag magnet. The leather is more worn now. The flag pin is chipped at one corner. But together they remind me who I was, who I am, and who I refuse to become.

Brandon once raised a glass and joked that the old man had finally learned his lesson.

He was right about one thing.

Someone learned a lesson out there at that cabin.

It just wasn’t me.

News

My father-in-law cut me out of family photos at our daughter’s first birthday. “Real family only,” he said. My wife didn’t defend me. I left the party early. By the time they needed me to co-sign their mortgage refinance, I was already filing for divorce.

My name echoed through the university arena, sharp against the floodlights, as I walked across that stage expecting—hoping—to see them….

My father-in-law cut me out of family photos at our daughter’s first birthday. “Real family only,” he said. My wife didn’t defend me. I left the party early. By the time they needed me to co-sign their mortgage refinance, I was already filing for divorce.

My name echoed through the university arena, sharp against the floodlights, as I walked across that stage expecting—hoping—to see them….

My father-in-law cut me out of family photos at our daughter’s first birthday. “Real family only,” he said. My wife didn’t defend me. I left the party early. By the time they needed me to co-sign their mortgage refinance, I was already filing for divorce.

My name echoed through the university arena, sharp against the floodlights, as I walked across that stage expecting—hoping—to see them….

I refused to go on the family vacation because my sister brazenly brought her new boyfriend along – my ex-husband who used to abuse me; “If you’re not going, then give the ticket to Mark!” she sneered, and our parents backed her up… that night I quietly did one thing, and the next morning the whole family went pale.

The night my mother’s number lit up my phone for the twenty-ninth time, I was sitting on my tiny city…

my husband laughed as he threw me out of our mansion. “thanks for the $3 million inheritance, darling. i needed it to build my startup. now get out – my new girlfriend needs space.” i smiled and left quietly. he had no idea that before he emptied my account, i had already…

By the time my husband told me to get out, the ice in his whiskey had melted into a lazy…

My father suspended me until I apologized to my sister. I just said, “All right.” The next morning, she smirked until she saw my empty desk and resignation letter. The company lawyer ran in pale. Tell me you didn’t post it. My father’s smile died on the spot.

My father’s smile died the second he saw my empty desk. It was a Thursday morning in late September, the…

End of content

No more pages to load