By the time I heard the banging, the iced tea ring was still on the kitchen counter and the little American flag magnet on our fridge was exactly where I’d left it, holding my wife’s crooked grocery list in place. Two weeks earlier I’d walked out of this same front door with Sinatra playing low on the Bluetooth speaker, telling Margaret I’d be back before she had time to miss me. Now the house was dark, the September air felt wrong, and the sound coming from the basement door didn’t belong in any normal home.

At first I thought it was the air conditioner or the washing machine kicking on. Then I heard it again—three dull, uneven thuds, then a pause, then three more. Not loud, but desperate. I dropped my suitcase, heart hammering against my ribs. “Margaret?” I called out, but the house swallowed my voice. The banging came again, clearer this time, and underneath it a thin, ragged voice I barely recognized. That was the moment I knew I wasn’t walking into my own living room. I was walking into a crime scene.

I wish I could tell you I reacted like some coolheaded movie hero. The truth is, my hands were shaking so badly I fumbled the deadbolt twice before I got the front door open. I’m sixty-five, retired, and more used to drafting engineering plans than breaking into my own basement. But when you hear your wife sounding like she’s clawing her way out of a grave below your feet, you don’t think; you just move. That’s the first hinge in this story, the quiet moment where a normal life snaps in half.

The house smelled stale, like it had been closed up for a month, not fourteen days. No lamps on in the living room. No TV murmuring in the background. No soft shuffle of Margaret’s slippers. The only light came from the street through the blinds, cutting long gray stripes across the hardwood floor. I stepped inside, letting the door slam shut behind me, and the sound from below hit me full force.

Thud. Thud. Thud.

Then, hoarse and ragged: “Help… please…”

The voice was so dry it sounded like sandpaper, but it was my wife. I knew it in my bones. “Margaret!” I shouted, my own voice coming out higher than I expected. I followed the sound down the hallway to the basement door, and that’s when I saw the padlock. A heavy-duty, silver thing bolted through a metal hasp drilled right into the doorframe. We’d lived in this house in the suburbs of Tacoma for twenty years. I’d never seen that lock in my life.

For a split second, my brain tried to rationalize it. Maybe a contractor? Maybe my daughter had locked something in the basement for safety? Maybe… I reached out and grabbed the lock. It was solid, cold, and very, very real. On the other side of that door, my wife hit something with what sounded like the last of her strength.

“Hang on, honey!” I yelled. “I’m here, I’m right here!”

My fingers were too clumsy to work the combination or key or whatever it needed, so I didn’t bother. I sprinted to the garage, nearly tripping over my own suitcase, and grabbed the old crowbar that had been hanging on the pegboard since the kids were little. Two swings went wild and slammed into the doorframe. The third hit metal, the impact shooting up my arms. On the fourth, the hasp gave. The lock hit the floor with a dead, final clank.

The smell hit me before the light did. Urine. Sweat. Something sour and wrong, the way a hospital room smells at three in the morning when nobody’s opened the window in hours. I flipped the basement light switch and for a second nothing happened. Then a single bulb flickered on halfway down the stairs, casting a sickly yellow cone that stopped three steps shy of the concrete floor.

“Thomas?”

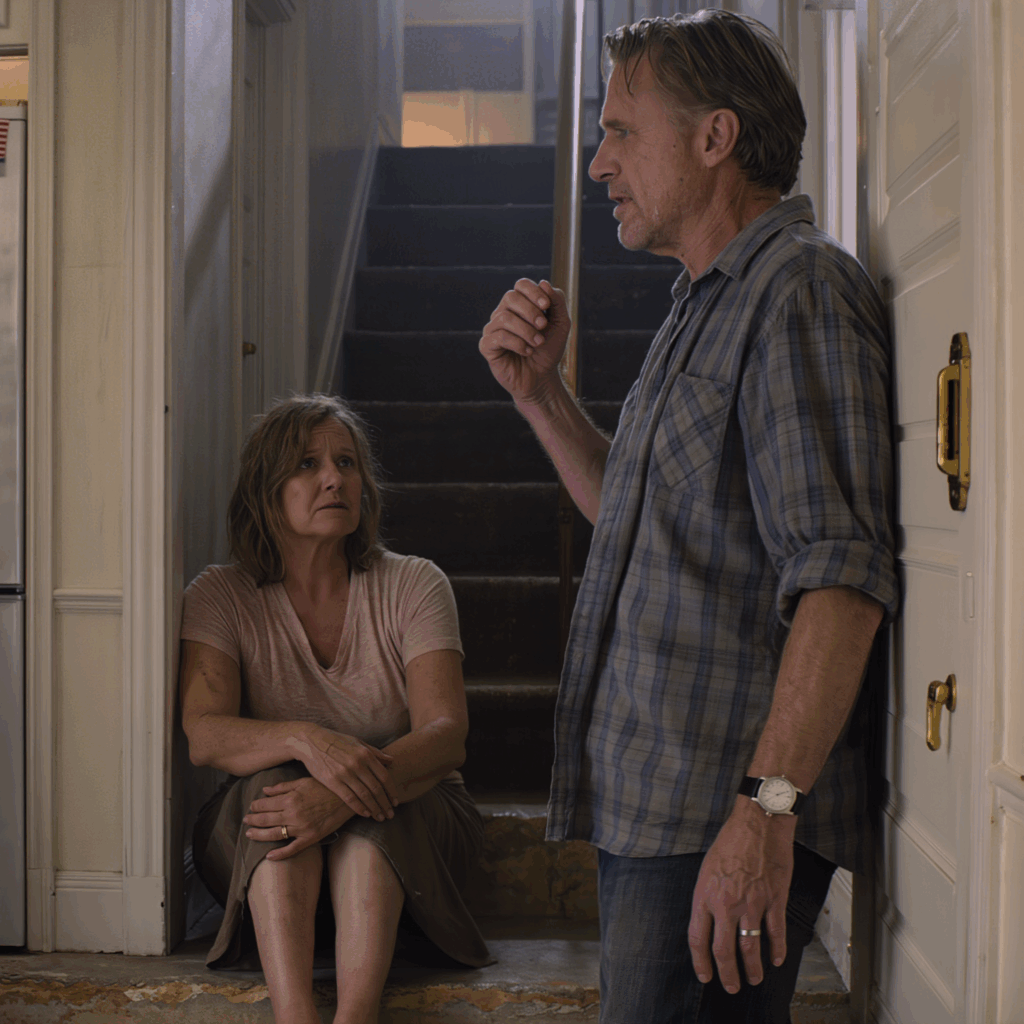

My name came out of the dark like a question someone had been afraid to ask. I took the stairs two at a time, my knees protesting, grabbed the railing so hard my knuckles went white, and there she was. Margaret was huddled at the base of the stairs in her nightgown, the blue one with tiny white flowers she always liked. It was filthy, stained dark in places I didn’t want to think about. Her face was gaunt, eyes sunken, lips cracked and bleeding. Her gray hair, usually soft and brushed, hung in greasy strings around her face.

She looked up at me, squinting against the light, like I was a stranger breaking into her nightmare. “Is that… really you?” she whispered.

I dropped to my knees on the cold concrete. “Yeah, baby. It’s me. It’s Thomas. I’ve got you.” She weighed almost nothing when I pulled her into my arms. Margaret used to tease me that I married her because she was tall enough to dance with without me having to stoop. Now she felt like a bundle of twigs.

“How long have you been down here?” I asked, though I already knew the answer I couldn’t handle.

She blinked slowly. “It’s been… dark,” she said, the words dragging themselves out of her throat. “I kept calling… you weren’t home. Jenny said… Jenny said you were busy.”

I felt something inside me tear. Our daughter, Jennifer—Jenny when she was eight and missing her front teeth and terrified of thunder. I pushed that picture out of my mind. There’d be time for that later. Right now the only thing that mattered was the woman in my arms.

“I’m calling 911,” I said, more to myself than to her. I scoop-carried her up the stairs, every step a prayer that I wasn’t too late. In the kitchen, the American flag magnet still held Margaret’s grocery list—milk, eggs, her favorite iced tea—like some cruel joke. The ordinary world was still pinned in place while ours had fallen straight through the floor.

I laid her gently on the couch, grabbed my phone with shaking hands, and punched in 9-1-1. My voice sounded strange in my own ears when the dispatcher answered. “My wife’s been locked in our basement,” I said. “She’s dehydrated, she’s confused, she has early-onset Alzheimer’s. Please, just send somebody. Please.”

The dispatcher was calm, steady, professional, the way people get when they’ve heard every kind of panic before. She asked my address, asked if Margaret was breathing, conscious, bleeding. I answered on autopilot, one hand on the phone, the other on my wife’s shoulder. “Stay with her, sir,” the dispatcher said. “Help is on the way.”

That was the second hinge in the story: the moment I stopped being a husband who’d been gone too long and became the man who’d left his wife to be locked in a tomb under his own feet.

The paramedics made it to the house in under ten minutes, but it felt like an hour and a half. I watched the red and blue reflections from the ambulance lights slide over the front window blinds, turning our quiet cul-de-sac into something out of a crime drama. I’d watched those shows before, sitting on this same couch with Margaret, a glass of iced tea sweating on the coffee table, the flag magnet crooked behind us on the fridge. I never thought I’d be the one opening the door for first responders.

They came in with their bags and their calm voices and their efficient movements. “Sir, I’m Kelly, this is Drew. We’re with the fire department. Where’s your wife?” Kelly’s eyes took in the scene in a single sweep—the open basement door, the broken lock on the floor, the smell that still lingered.

“Right here,” I said, stepping aside.

They checked her vitals, clipped a pulse oximeter to her finger, took her blood pressure. Kelly’s forehead creased. “Pulse is weak. She’s severely dehydrated. Skin turgor’s bad. How long has she been like this?”

“I—I don’t know,” I stammered. “I’ve been gone for two weeks. I just found her. She has Alzheimer’s, but she was… she was okay when I left. I thought she was okay.”

Kelly looked up at me. “When did you last talk to her?”

“Fourteen days ago.” The number slid out of my mouth like a confession. Fourteen days. Two weeks. Three hundred and thirty-six hours my wife had spent in the dark while I slept in a hospital chair a thousand miles away, thinking I was doing the right thing.

They loaded her onto the stretcher and wheeled her out. I rode in the front of the ambulance, white-knuckling the grab bar while the driver flipped on the siren. Every bump in the road felt like a judgment. Sinatra would’ve called it fate, but it felt a lot more like failure.

At the ER, everything moved fast and slow at the same time. Nurses met us at the bay doors, peppering me with questions as we rolled down bright hallways that smelled like antiseptic and overcooked coffee. “Any recent illnesses? Medications? Allergies?” I answered what I could and guessed at what I couldn’t. Margaret disappeared behind a curtain, and I was left standing in the middle of an emergency room, holding a plastic bag with her shoes in it.

A doctor in blue scrubs came out after what felt like forever. “Mr…?”

“Holloway,” I said. “Thomas Holloway.”

“I’m Dr. Patel,” she said, her voice gentle but serious. “Your wife is severely dehydrated and malnourished. She has early signs of hypothermia. We’re giving her IV fluids and warming her up. She’s stable for now, but I need to ask—how did she end up locked in a basement?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I was in Phoenix. My mother had a stroke. I left our daughter here with Margaret. She was supposed to stay at the house, take care of her.” I heard my own voice getting sharper with each word, like if I pressed hard enough, the truth might pop out fully formed.

Dr. Patel’s eyes hardened just a fraction. “I’m going to have to contact Adult Protective Services and the police,” she said. “Given your wife’s condition and what you’ve described, this could be a case of elder abuse.”

“Elder abuse?” The term hit me like a slap. Margaret is sixty-three, two years younger than I am. We still have baseball caps from Mariners games, still have a playlist of Sinatra and Motown for Sunday afternoons, still have that stupid flag magnet we bought at a Fourth of July flea market. I didn’t think of her as elderly. “She has Alzheimer’s, but she’s… she’s still her.”

Dr. Patel nodded. “Exactly,” she said. “Which makes what happened to her even more serious.”

That was the third hinge: the moment I learned there’s a whole vocabulary for what happens when families turn on their own, and my daughter’s name was about to be written in that language.

A couple of hours later, after Margaret had been admitted and tucked into a room on the medical floor, a man in a blazer and slacks found me in the waiting area. I was sitting under a framed print of an American flag, its colors muted behind glass, sipping terrible vending machine coffee and staring at nothing.

“Mr. Holloway?” he asked.

“Yeah?”

He held out a badge. “I’m Detective Ray Morrison with the county sheriff’s Elder Crimes Unit. The hospital called us in. Mind if we talk?”

I didn’t mind. I needed to say it out loud to someone who might do more than nod sympathetically. We sat down in two plastic chairs under that framed flag, the kind of decoration that’s supposed to make everyone feel safe and patriotic. I’d never noticed before how small it looked.

Morrison took out a notebook. “Can you walk me through what happened tonight? Start from when you got home.”

So I told him. I talked about the dark house, the banging, the padlock, the crowbar, the smell, Margaret at the bottom of the stairs. I told him about the two weeks in Phoenix, sleeping in a recliner next to my mother’s hospital bed while my sister and I took turns holding her hand. I told him about leaving Margaret in Jennifer’s care.

“Jennifer is your daughter?” he asked.

“Our only child,” I said. “She’s thirty-eight. CPA. Lives about twenty minutes away with her husband, Kyle.” I could hear the pride in my voice, leftover from before tonight, and it made me sick.

“What arrangements did you make with her before you left?”

“She volunteered,” I said. “Soon as I told her about my mom’s stroke. ‘Dad, don’t worry about a thing,’ she said. ‘I’ll move into the house while you’re gone. I’ll take care of Mom. You just focus on Grandma.’” I remembered the way my chest had loosened when she said it, like someone had taken the crowbar to my fear and pried it off.

“Did she know about your wife’s routines? Her medication schedule?”

“Of course,” I said. “Jenny grew up in that house. She knows where the pill organizer is, knows the difference between Margaret being forgetful and Margaret being truly lost. We talked every day that first week. She’d put Mom on the phone, and Margaret sounded… tired, but okay. The second week, Jenny stopped picking up. She’d text instead—‘Busy with Mom, she’s good, call you later.’ Only she never called later.”

Morrison’s pen scratched across his notebook. “Did you give your daughter power of attorney over your wife’s affairs while you were gone?”

The question blindsided me. “No,” I said. “Absolutely not. We talked about doing it someday, in case something happened to me first. But we never signed anything. Why?”

“Did your wife sign any documents you’re aware of in the last month? Anything at all?”

“Not that I know of,” I said. “She gets confused with forms. I usually handle that stuff.”

Morrison tucked his pen behind his ear and closed the notebook. “Mr. Holloway, I don’t want to jump to conclusions,” he said carefully, “but I’ll be honest with you. A lot of the elder abuse cases we see aren’t strangers. They’re family. Adult children. In-laws. Caregivers who’ve been around for years.”

“You think Jenny did this?” I asked, my voice coming out in a whisper. “You think my daughter locked her mother in a basement?”

“I think,” he said, “that your wife didn’t install that padlock herself. I think your daughter had full access to your home and your accounts. And I think, given your wife’s condition, someone saw an opportunity. We’re going to need to look at your finances, your home, your daughter’s place. Do I have your permission to start digging?”

I stared at the framed flag on the wall, the red stripes blurring. When Jennifer was little, she used to stand in our driveway on Memorial Day waving a tiny paper flag, asking me to play Sinatra’s “The House I Live In” on the stereo. I used to tell her that in this country, you look out for your own. We grill for neighbors, mow each other’s lawns, sit with them in hospital waiting rooms. We don’t lock our mothers in basements.

“Dig,” I said. “Dig until you hit bottom.”

That was hinge number four: the moment I stopped hoping this was some horrible misunderstanding and started praying there was a paper trail strong enough to hang the truth on.

Margaret spent three days in the hospital. They warmed her up, pumped her full of fluids, and started her on a gentle diet. Physically, she rallied faster than anyone expected for a woman who’d been treated like a piece of forgotten luggage. Mentally, though, the damage was more complicated. She kept asking for Jenny.

“Is she coming for dinner?” Margaret would ask, her voice soft and hopeful. “She said she was making spaghetti.”

“Not tonight, sweetheart,” I’d answer, smoothing her hair back from her forehead. “Just rest. I’m here. I’m not going anywhere.”

Sometimes she’d frown, confused. “But Jenny was just here,” she’d insist. “She said she needed me to sign something for you. For the house. Did I do something wrong?”

Every time she said that, it was like another nail in a coffin I hadn’t wanted to believe was real.

On the second day, while Margaret finally slept, a nurse suggested I go home, shower, change clothes, maybe grab a real meal. “You’ll be a better caregiver if you’re not running on fumes,” she said. She meant well. I drove home with my chest tight the entire way.

The house smelled even worse without the adrenaline to cover it. The broken lock still lay on the floor by the basement door, a little metal tombstone for the life we’d had before. I forced myself to walk down those stairs again. I needed to see, really see, what my wife had lived in for fourteen days.

The light bulb at the bottom of the stairs had been unscrewed and left hanging dead in the socket. No wonder Margaret kept talking about the dark. In the corner was a five-gallon bucket, half full of waste. A thin blanket lay on the concrete floor, barely thicker than a beach towel. No food trays. No water bottles. No sign that anyone had even tried to make her captivity survivable.

On the inside of the basement door, just above the reach of someone sitting on the floor, were faint white scratches. Fourteen vertical lines, clustered together. I ran my fingers over them, feeling the rough edges. Once for each day, my brain supplied, because apparently it hated me.

That was hinge five: the moment fourteen stopped being a number on a calendar and became a set of claw marks on a door.

Upstairs, the kitchen looked mostly normal at first glance. The flag magnet still held Margaret’s list, though the paper had curled at the edges. There were a few extra dishes in the sink, a pair of wineglasses on the counter, an empty takeout bag in the trash. Nothing screamed “crime” until I saw Jennifer’s laptop on the table.

It was open, screen dark, charger still plugged into the wall. Jenny never went anywhere without that thing. Seeing it abandoned in my kitchen was like finding her wallet on the sidewalk. I hesitated for half a second. I’m not the snooping type. I grew up in a different generation, one where you didn’t read other people’s mail.

Then I pictured Margaret at the bottom of those stairs, calling for me until her throat went raw, and whatever moral hesitation I had burned up on the spot.

The password was saved. Of course it was. Once the screen woke up, it took me three clicks to find a folder called “Documents” and another one called “Mom.” Inside were scanned PDFs, spreadsheets, a subfolder labeled “Investment Opportunity – Kyle’s Fund.” My stomach dropped.

I opened the first PDF. It was a power of attorney document, giving Jennifer full control over Margaret’s financial and medical decisions. The signature at the bottom was my wife’s—shaky, yes, but undeniably hers. The date was from the first week I’d been in Phoenix.

There was a note in Jenny’s handwriting in the margin of a scan: “Mom, this just lets me help Dad with the paperwork while he’s gone. Nothing changes. – J”.

Next were bank statements. Our joint savings account, the one Margaret and I had built slowly over four decades of work, birthdays skipped, vacations postponed. Seventy-five thousand dollars withdrawn in three separate transfers. Our home equity line of credit—one hundred thousand dollars drawn against the house we’d paid off fifteen years ago. The line that used to say “Balance: $0” now said “Balance: $100,000.” My palms went cold.

All of it—$175,000 in total—had been transferred to an account in the name of “Thornhill Capital Management, LLC.” I clicked deeper. Thornhill’s website was slick, full of stock photos of smiling retirees and glowing descriptions of “cutting-edge cryptocurrency strategies” and “passive income streams.” At the bottom of the “About” page was a blurry picture of Kyle in a navy blazer, hand extended like he was about to shake yours and take your wallet.

The business address was a rented mailbox store.

I kept clicking, fingers numb. In Jennifer’s email, I found exchanges with a notary who’d witnessed Margaret’s signature on the POA. A few searches later and I knew the office was a strip-mall shop twenty minutes away, the kind of place that cashes checks and wires money and doesn’t ask too many questions as long as the IDs look vaguely real.

Then I found the text messages.

Kyle: “She keeps crying for your dad. This isn’t going to work.”

Jennifer: “She’ll forget. Give it another day. The confusion helps.”

Kyle: “What if someone checks on her?”

Jennifer: “Who? Dad’s in Phoenix. Mom’s friends haven’t visited in months. We’re fine.”

I read that last line three times, each word sinking in separately. We’re fine. The bucket in the corner, the unscrewed light bulb, the scratches on the door—those were fine. Margaret’s cracked lips and sunken eyes were fine. My wife’s suffering was a temporary inconvenience in their spreadsheet.

I don’t remember dialing Detective Morrison’s number, but suddenly he was on the line and I was talking so fast I had to start over twice.

“Slow down, Mr. Holloway,” he said. “You’re saying you found POA documents and bank transfers?”

“And texts,” I said. “They locked her down there on purpose. To keep her from talking to me. They cleaned out our savings, took a hundred grand out of the house, and wired it all to Kyle’s fake company. And they were just going to leave. They were going to let her die down there.”

There was a pause on the line, the kind that says someone is choosing their words carefully. “Stay put,” Morrison said. “I’m on my way, and I’m bringing a warrant.”

If the first time he’d come to see me I’d felt like a worried husband, this time I felt like a plaintiff in a lawsuit I hadn’t filed yet. Or a witness. Or maybe a father who’d finally let himself believe his daughter was capable of something unspeakable.

Morrison arrived with two uniformed deputies and a folder full of paperwork. They photographed everything—the broken lock, the basement, the bucket, the tally marks on the inside of the door. They bagged the unscrewed light bulb as evidence, like it was a weapon. They asked me to step aside while a tech cloned Jennifer’s laptop.

“This is more than just neglect,” Morrison said quietly, standing in my kitchen with the flag magnet over his shoulder. “We’re looking at elder abuse, unlawful imprisonment, financial exploitation, probably fraud. I’m going to loop in the district attorney’s office. Where do your daughter and her husband live?”

I gave him the address of their condo across town. “You think they’re there?” I asked.

He checked his watch. “Maybe,” he said. “If they’re smart, they’re already on the move. People who plan this much rarely sit still once the money’s gone.” He made a call, rattling off codes and addresses I barely heard. When he hung up, he looked at me. “You said you came home three days earlier than planned?”

“My mom rallied,” I said. “The doctors in Phoenix thought she’d be in the ICU longer, but she improved. My sister told me to come home, get some rest. Why?”

“Because if you’d stuck to your original return date,” he said, “we might’ve been dealing with a very different situation. Your early flight home probably saved your wife’s life.”

That was hinge number six: the realization that a random change in plane tickets stood between us and a funeral.

The deputies didn’t find Jennifer and Kyle at their condo. What they did find was almost worse. The place was half emptied out—closets bare, drawers pulled, a couple of suitcases missing from the bedroom closet. On the kitchen counter, in a pile ready for trash day, they found shredded drafts of bank statements, a printout of one-way tickets from Seattle to New York and then on to Lisbon, and an email from a property management company in Portugal confirming a six-month furnished rental by the beach.

“They were running,” Morrison told me over the phone that night. “We’re issuing warrants for both of them. We’ve flagged their passports. If they try to leave the country through any major airport, TSA will snag them. In the meantime, I need you to brace yourself. This is going to get very public very fast.”

He wasn’t kidding. Within forty-eight hours, local news stations were running segments on “Alleged Elder Abuse and Financial Fraud in Tacoma Suburbs.” They showed my house from the street, blurring the address but leaving the American flag wind sock on our front porch fully visible for everyone on our block to recognize. They used Margaret’s photo from her driver’s license—before the Alzheimer’s, before the basement—and the mugshots of Jennifer and Kyle once the warrants went live.

Neighbors started texting. People from my old engineering firm called, some to offer help, some just to say they’d seen the story and couldn’t believe it. The pastor from our church left a voicemail promising prayers. A woman from Adult Protective Services came by the hospital to introduce herself and hand me pamphlets I couldn’t bring myself to read yet.

The only person who didn’t call was Jennifer.

Margaret came home on the fourth day, frailer but upright, clutching the hospital blanket like a security item. I’d hired a full-time caregiver, Maria, to help during the day, at least until we could figure out what the long-term plan was. Alzheimer’s doesn’t pause for legal proceedings.

The first night back, Margaret shuffled into the kitchen, paused in front of the fridge, and stared at the flag magnet and her old grocery list. “I was going to make you iced tea,” she said, voice puzzled. “Did I forget?”

“No,” I said softly, gently turning her back toward the living room. “You didn’t forget. Someone else did.”

That flag magnet became more than a cheap souvenir in that moment. It was the line between the life we thought we had and the one we were actually living.

On day six, just as Margaret was asking if Sinatra could “do that song about summer again,” my phone rang. It was Detective Morrison. “We’ve got them,” he said. “TSA flagged your daughter and son-in-law at Sea-Tac. They were trying to board that flight to New York and then Portugal. They’re in county lockup right now, waiting to be arraigned.”

I turned Sinatra off and sat down hard. “Okay,” I said. “Okay.” I didn’t feel triumphant. I didn’t feel vindicated. I felt like I’d just watched my kid step out in front of a truck in slow motion and I’d only managed to grab the back of her shirt after it was too late.

The arraignment was the first time I saw Jennifer in an orange jumpsuit. She shuffled into the courtroom with her hands cuffed in front of her, a deputy on each side. Kyle followed, looking smaller without his slick blazer and borrowed confidence. I sat in the second row, behind the assistant district attorney, trying to breathe.

The judge read the charges out loud: elder abuse of a dependent adult, unlawful imprisonment, financial exploitation, fraud over $5,000, forgery. Kyle had an additional stack tied to securities fraud and operating an unlicensed investment fund. The ADA, a sharp woman named Patricia Ross, recommended they be held without bail given the flight risk.

Jennifer’s lawyer argued the opposite. He talked about her lack of prior record, her ties to the community, her supposed cooperation. He said words like “misunderstanding” and “family dispute” that made my skin crawl. Jennifer kept turning in her seat, trying to catch my eye. At one point she mouthed, “Dad, please.” I stared at the prosecutor’s legal pad instead.

When the judge denied bail and ordered them held at the county detention center, Jennifer sagged in her seat. Kyle just stared straight ahead. That was hinge number seven: the moment I realized justice doesn’t look like a movie climax. It looks like paperwork and handcuffs and your daughter being led through a side door you’re not allowed to follow.

The criminal case rolled forward like a machine, but there was more to do than sit in court and wait. Patricia called me into her office a week after the arraignment to walk me through their strategy. Her office was small, cluttered with files, and decorated with a single framed picture of her kids in front of a backyard grill, an American flag hung crookedly on the fence behind them. Apparently those things follow you.

“This is one of the worst cases I’ve handled,” she said without preamble. “The planning. The use of your wife’s cognitive impairment. The confinement. The financial damage. We’re pushing for maximum sentences.”

“What does that look like?” I asked.

“Realistically,” she said, “for Jennifer, eight to twelve years in state prison. For Kyle, ten to fifteen, given the additional fraud victims in his so-called fund.” She flipped through a file. “We’ve identified at least thirty other investors, most of them retirees, all of them told they’d double their money in crypto within a year. He was running a classic Ponzi scheme. Your funds were basically fresh meat.”

I swallowed. “And the money?” I asked. “Can we get it back?”

Her expression softened. “We’ll pursue restitution in the criminal case,” she said. “You should also consider a civil suit for the full amount plus damages. But, Mr. Holloway, I need you to be realistic. The money’s been spent, moved, or used to pay off earlier investors. There’s not a bank account somewhere with your name on it waiting to be unlocked.”

A week later, I sat in another attorney’s office, this one belonging to Christopher Walsh, a gray-haired civil litigator who specialized in elder law. He listened, took notes, and then leaned back.

“You sue,” he said simply. “You sue them both for every penny they took and every ounce of pain they caused. Even if they don’t have assets now, they might in the future. Wages, inheritances, property. You get a judgment and you attach it to their names like an anchor. They chose this. They can carry it.”

“Is that… revenge?” I asked.

“You can call it that if you want,” he said. “I call it accountability. They used legal tools—power of attorney, home equity—to hurt your wife. You get to use legal tools to protect her.”

That night, after I’d signed the retainer and Maria had helped Margaret to bed, I stood in the kitchen staring at the flag magnet again. The grocery list was still there, curling more at the edges now. I took it down, smoothed it on the counter, and wrote a new list beneath Margaret’s handwriting: “1. Criminal charges. 2. Civil suit. 3. CPA license.”

That was hinge number eight: the moment I turned grief into a to-do list.

The civil suit went in two weeks later: Thomas and Margaret Holloway, plaintiffs, versus Jennifer Holloway and Kyle Walker, defendants. Claims: financial exploitation, conversion, breach of fiduciary duty, intentional infliction of emotional distress. Damages sought: $175,000 in stolen funds plus $200,000 in additional damages. The numbers looked obscene on paper, not because they weren’t accurate, but because I couldn’t believe I was suing my own daughter.

I also filed a formal complaint with the State Board of Accountancy. Jennifer had used her CPA license to give Kyle’s fake fund a veneer of legitimacy. She’d recruited two of her coworkers as investors, assuring them she’d personally reviewed the books. Apparently she had—just not in the way they thought.

Within a month, the board had suspended her license pending the outcome of the criminal case. The letter they sent me said that if she was convicted, she’d be permanently barred from practicing as a CPA in the state. I didn’t feel triumphant when I read it. I just felt like I’d checked off another item on that grim little list.

Outside the world of courtrooms and legal letters, life went on in small, grinding ways. Margaret’s Alzheimer’s, already creeping forward, lurched ahead under the stress. Her neurologist told me trauma can accelerate decline. She stopped asking for Jennifer as often, which was somehow worse than the questions. It was like her brain had decided erasing our daughter was safer than remembering her.

Our finances, once boring and predictable, became a monthly math problem I was never quite sure I’d solved right. Medical bills, legal fees, and the freshly minted mortgage payment on the home equity line we’d never wanted all stacked up like a Jenga tower missing pieces. I picked up part-time consulting work, reviewing engineering plans for a local firm. Maria agreed to a slightly lower rate after I showed her the bills. Pride turned into a luxury I couldn’t afford.

The midpoint of this story didn’t come with dramatic music. It came on a Tuesday afternoon in January, when I walked into the bank to refinance what was left of our house. The loan officer was kind, sympathetic, and very good at pretending not to recognize me from the news.

“We’ll get you the best terms we can,” she said, sliding a stack of disclosures across the desk. “Given your age and income, it’s going to be tight, but doable.” She paused. “Mr. Holloway, I’m so sorry. My parents are about your age. I can’t imagine.”

“I used to think I couldn’t either,” I said. “Now I try not to imagine anything. I just sign where they tell me.” That was hinge number nine: the day I realized my revenge wasn’t a single moment, but a thousand small, humiliating tasks required just to keep the lights on.

The preliminary hearing for Jennifer and Kyle happened a few weeks later. I’d never been in a courtroom this often in my life. Patricia walked me through what to expect. “This isn’t the trial,” she said. “We’re just establishing there’s enough evidence to proceed. But your testimony matters.”

I took the stand, swore to tell the truth, and told it again. I talked about the flight to Phoenix, the nightly calls, the texts that replaced them. I described finding the padlock, the smell, the tally marks on the door. I walked the judge through the bank transfers, the POA, the texts about confusion helping.

Jennifer sat at the defense table, hair pulled back, wearing a plain blouse the jail must have provided. She stared at a point just over my shoulder, jaw clenched. Kyle sat beside her, staring down at his hands.

Her attorney tried to paint her as overwhelmed, manipulated by Kyle, struggling with anxiety and depression. He asked if I’d noticed any emotional problems growing up, suggested she might have been desperate and not thinking clearly.

“She was desperate,” I said. “Desperate enough to lock her mother in the dark for two weeks so she could steal from her. That’s not a panic attack. That’s a plan.” Even the court reporter looked up at that.

The judge agreed with Patricia. There was more than enough to go to trial. Jennifer and Kyle were remanded back to custody. As we filed out, Jennifer finally looked straight at me.

“Dad,” she called softly. “Please. Don’t do this. We’re family.”

I didn’t answer. I just kept walking, past the flag in the corner of the courtroom, past the portraits of judges, past the metal detector humming at the entrance. Whatever family we’d been, she’d padlocked it shut from the outside.

Spring rolled around, bringing cherry blossoms to our street and subpoenas to my mailbox. Patricia called one afternoon with news. “Kyle’s attorney reached out,” she said. “He wants a deal. He’ll plead guilty to all charges and cooperate fully in testifying against Jennifer in exchange for a reduced sentence.”

“So he’ll blame her to save himself,” I said.

“He’s already blaming her,” she replied. “This just puts it on the record. The question is whether his testimony makes your daughter’s conviction more certain. I won’t make this call without you.”

“Will he go to prison?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said. “We’re offering eight years. With good behavior and parole, he’ll serve at least five.”

“And Jenny?”

“With his testimony and the rest of the evidence, we’re asking for the max—twelve years. Without him, there’s always some risk with a jury. With him, that risk shrinks.” She paused. “I know this is brutal. I wish there were an option that spared you this.”

I looked through the kitchen window at Margaret sitting on the back porch with Maria, staring up at the sky like she was trying to remember the names of the clouds. Fourteen days in the dark hung between us every time she squinted at a shadow. “Take the deal,” I said. “If he’s going to tell the truth, let him tell it under oath.”

Kyle pled guilty in February. At his sentencing, he read a statement about remorse and bad decisions and addiction to risk. His lawyer probably wrote half of it. The judge listened, nodded, and then laid it out plain.

“You targeted vulnerable people,” she said. “You used their trust, their age, and their lack of familiarity with new financial tools as leverage. You didn’t just steal money. You stole peace of mind. Eight years in state prison is not excessive. It’s merely proportionate.”

One down, I thought, then immediately hated myself for the scoreboard in my head.

Jennifer’s trial started in June. The courtroom was cooler than the air outside, but sweat beaded at the back of my neck anyway. The same flag hung behind the judge’s bench. A new jury filled the box, a dozen strangers who were about to learn more about my family than some of my relatives knew.

Patricia opened with a story so simple it cut through every legal technicality. She told them about Margaret: her diagnosis, her routines, her confusion. She told them about my trip to Phoenix, about Jennifer volunteering to help, about the padlock, the basement, the tally marks. She put fourteen days on the record.

Then she started calling witnesses.

Dr. Patel testified about Margaret’s condition when she arrived in the ER. The Adult Protective Services worker explained why Margaret’s vulnerability made the confinement especially cruel. The bank manager walked the jury through the transfers, the POA, the home equity line of credit that had turned our paid-off house into a debt machine.

Then it was Kyle’s turn.

He told the jury Jennifer had come up with the idea. “She said her mom wouldn’t know the difference,” he testified, eyes fixed on a spot on the wall. “She said with her dad out of town, it was the perfect time to handle the paperwork. She researched power of attorney laws, found a notary that didn’t ask too many questions, and coached her mom on signing.”

He described Margaret crying for me the second day she was locked in the basement. “I told Jenn this was messed up,” he said. “She told me her mom’s confusion made it easier. She said, ‘The disease already took her. We’re just making sure it doesn’t take us down with her.’” A juror in the front row flinched.

Jennifer’s attorney tried to shake him, suggesting he was shifting blame. But the digital footprints backed him up—Jennifer’s laptop history full of searches about elder exploitation laws, extradition treaties, and

“countries where financial crimes go unpunished.” She’d even bookmarked an article titled “Why Portugal Is the New Haven for Crypto Entrepreneurs.” The jurors didn’t need law degrees to see the pattern.

Then Margaret took the stand.

Getting her there had been a discussion that lasted weeks. Her neurologist warned us that the stress could make her worse. Patricia said her testimony, even confused, could be powerful. In the end, Margaret herself made the decision one of her clearer mornings.

“If they’re talking about me,” she said, “I should be there, right?” She smiled faintly. “I always hated when people talked about me like I wasn’t in the room.”

Maria helped her to the witness stand. She held onto the rail like she was boarding a boat. The bailiff asked if she swore to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. Margaret nodded. “I’ll try,” she said.

Patricia asked gentle questions. Margaret answered as best she could. She remembered the basement as “the cold place” and “the dark,” remembered calling for me until her voice went away, remembered being thirsty. She remembered Jennifer at the top of the stairs once, a silhouette against the light.

“She said you were busy,” Margaret murmured. “Jenny said you were taking care of Grandma and I had to help by staying down there. I wanted to help. I just wanted to go upstairs too.” Her voice cracked on the last word.

Jennifer’s attorney tried to use Margaret’s confusion against her. He pointed out the details she couldn’t recall, the gaps in her timeline. Patricia let him dig for a minute, then calmly introduced the video.

Detectives had filmed the basement the day they executed the search warrant—the bucket, the blanket, the tally marks, the unscrewed bulb. The jury watched in silence as the camera panned slowly across the concrete. One juror wiped her eyes. Another stared at Jennifer like he’d never seen anything like her before.

“Mrs. Holloway may not remember every detail,” Patricia said softly when the video ended, “but that basement remembers. And so does every claw mark on that door.” That was hinge number ten: the moment the room turned.

Jennifer took the stand against her attorney’s advice. I could tell he’d argued against it by the way his shoulders slumped when she stood up.

She told the jury she’d been trying to help us, that Kyle had pressured her, that she’d panicked when the investments started going bad. She said she’d never meant to hurt anyone. She cried when she talked about Margaret, saying she loved her, that she’d just “made terrible choices under incredible stress.” Her voice wobbled in all the right places. If I hadn’t read those texts, I might have believed her.

Then Patricia walked up with a single sheet of paper.

“Miss Holloway,” she said, “is this your text message to your husband?” She read it aloud. “She’ll forget. Give it another day. The confusion helps.” She let the silence stretch. “You were referring to your mother, correct?”

Jennifer stared at the paper. “I was upset,” she said. “I didn’t mean—”

“You didn’t mean what?” Patricia asked quietly. “You didn’t mean for her to remember? You didn’t mean for your father to come home early? You didn’t mean for your plan to be interrupted before your mother died in that basement?” Her voice never rose, but each question landed like a hammer.

Jennifer broke then, full-on sobbing, the kind that makes your shoulders shake. “I just wanted to be free,” she choked out. “I was so tired of watching them fade, of feeling like my whole life was already gone. I just wanted out.”

Patricia let her cry for a beat. “You wanted out,” she said. “So you locked your mother in.” She turned to the jury. “The state rests.”

Deliberations took four hours. I spent them pacing the hallway, sitting in the hard wooden benches, refilling a Styrofoam cup with burnt coffee I didn’t drink. Margaret was at home with Maria, hopefully listening to Sinatra and not wondering where I was. I stared at the tiny flag pin on Patricia’s lapel as she came back down the hall. It was tilted, just like our magnet.

“They’re back,” she said.

The foreperson stood, hands trembling just slightly, and read the verdicts. Guilty on elder abuse. Guilty on unlawful imprisonment. Guilty on financial exploitation. Guilty on fraud. Guilty on forgery. The words blurred together into one long sentence in my head: You did this.

Jennifer’s shoulders slumped. For a second, she looked like she did when she was eight and I’d caught her lying about hitting a baseball through the neighbor’s window. Only this time, the broken glass was our entire life.

Sentencing came two months later. I submitted a victim impact statement—five pages typed, double-spaced, because apparently old habits die hard. I wrote about Margaret’s fourteen days in the dark, about the way she flinched at shadows now, about the way her neurologist said trauma had sped up the progression of her disease. I wrote about refinancing the house, about Maria’s paycheck sitting next to past-due notices, about the nights I lay awake counting backwards from fourteen and getting stuck on seven.

Margaret tried to write her own statement. She sat at the kitchen table with Maria, pen in hand, for nearly an hour. In the end, all she managed was “I was scared” in shaky letters that broke my heart. Her doctor sent a letter instead, explaining in clinical terms what the basement had done to her brain.

In court, Patricia read my statement aloud. I watched Jennifer flinch at some parts and stare blankly at others. Kyle sat in his orange jumpsuit, listening like the sound was coming from another room.

The judge took her time. When she finally spoke, her voice was measured, almost gentle, which somehow made it worse.

“Miss Holloway,” she said, “you are an educated woman. A licensed professional. A daughter. You understood your mother’s vulnerability. You understood your father’s trust. And you chose to exploit both. You locked a confused, dependent woman in a basement for fourteen days. You stole the money your parents had set aside to care for her in her final years. You planned to flee the country and leave them to pick up the pieces you shattered.”

She paused, letting the silence fill the room.

“There are crimes of impulse and crimes of calculation,” she continued. “This was the latter. I see no mitigating factors. On the counts before this court, I sentence you to twelve years in state prison. You will be eligible for parole under the usual guidelines, but I note for the record that the harm you caused cannot be undone in twelve years or any other number.” She turned to Kyle. “Mr. Walker, your eight-year sentence stands.”

The gavel came down with a crack that echoed off the wood paneling. That was hinge number eleven: the sound of a judge saying out loud what I’d barely let myself whisper.

Afterward, people asked if I felt relief. Closure. Vindication. The truth is, what I felt was tired. Bone-deep, marrow-level tired. Like every step out of that courtroom took more effort than pushing that crowbar against the lock on my basement door.

The civil case wrapped up a month later. The judge entered a judgment against Jennifer and Kyle for $375,000—$175,000 in stolen funds plus $200,000 in damages. The court put liens on any future wages, property, or inheritances they might receive. Realistically, I know what that means: pieces of paper saying we’re owed money that will probably never arrive.

Restitution in the criminal case ordered them to pay back the $175,000 with interest. Again, I’m not holding my breath. The Ponzi scheme is a crater, early investors clawing for whatever pennies are left. We’re all standing around the same burned-out building, wondering who lit the match.

Life now is smaller and sharper. Margaret’s Alzheimer’s has moved into its crueler stages. Some mornings she wakes up and smiles at me like she always has, asks if I want iced tea even if it’s December, hums along to Sinatra while Maria makes breakfast. Other mornings she looks at me with polite confusion and asks if I’m “the man from the bank.” The first time that happened, it lasted an hour. An hour in which the woman I’ve loved for forty-two years treated me like a stranger helping her sign forms she didn’t understand.

That was hinge number twelve: the moment I realized Jennifer hadn’t just stolen money or time. She’d stolen a piece of the last clear years Margaret and I had together.

Neighbors still wave when I walk the dog, but some of them cross the street a little sooner than they used to, as if the whole saga might be contagious. At church, people hug me longer than necessary, their eyes scanning my face for signs of bitterness or holiness. I’m not particularly rich in either.

Every now and then a reporter will call, asking if I want to comment on elder abuse, or financial scams, or the “rise of crypto fraud.” I always say no. I’m not a spokesperson. I’m a man who missed fourteen days he can never get back.

People ask, too, if I ever visit Jennifer. If I send her letters, if we talk on the phone, if I’ve forgiven her. I tell them the truth: I haven’t visited. I don’t write. I don’t answer the collect calls when the prison number pops up on my phone. Forgiveness is between her and whatever God she chooses to talk to in that cell. Accountability is between her and the state. And love—the kind I still have for Margaret, the kind that made me drive home from Phoenix early without knowing why—that’s what keeps me here, paying off debts I didn’t create.

On the fridge, the flag magnet is still there. The paper under it has changed. Margaret’s original grocery list hangs behind a newer one now, one Maria helped her write on a good day: “Milk, eggs, iced tea, Sinatra, Thomas.” She insisted on adding my name. “So I don’t forget,” she said.

I straightened the magnet last week. It had been crooked for so long I’d stopped seeing it that way. As I nudged it into place, I realized that stupid little rectangle of plastic had been the through-line all along—the ordinary thing that kept showing up in the background while everything else fell apart.

When people ask if I regret pushing for charges, for the max sentence, for the civil suit, for the license suspension—if I regret making sure every legal door slammed shut on my own daughter—I think about that magnet. I think about fourteen tally marks on a basement door. I think about iced tea rings on the counter and Sinatra humming while my wife hums along on the days she still remembers the words.

Do I regret it?

No.

My daughter locked her confused, terrified mother in the dark for fourteen days so she could steal the money we’d saved to take care of that same mother. She was willing to let Margaret die and call it an unfortunate tragedy on the way to her beach rental in Portugal. Twelve years in prison isn’t too harsh. It’s mercy.

I didn’t lay a hand on her. I didn’t scream at her in the courtroom or curse her name. I did something that, in its own way, hurt more. I told the truth, over and over, to anyone in a position to do something about it. I signed documents. I answered questions. I took every legal tool she’d twisted and used it to bend the world back toward something that resembled right.

She once told me, when she was a teenager angry about a curfew, that consequences were just another word for revenge grown-ups used to feel better about themselves. I didn’t argue with her then. I just took her car keys and waited for her to figure out I wasn’t bluffing.

Now, when people ask why I did it, why I didn’t find a way to “handle it as a family,” why I wasn’t more worried about how prison would change her, I finally have an answer.

I did it because consequences aren’t revenge. They’re the bill that comes due when you treat your family like collateral. They’re the only language some people understand once they’ve decided other people’s suffering is a line item in their budget.

So, no, I don’t regret calling 911. I don’t regret handing Morrison that laptop. I don’t regret sitting in courtrooms until my knees ached or signing civil complaints with hands that wouldn’t stop shaking. I don’t regret making sure the system saw my wife as a person and my daughter as what she chose to be.

Jenny once said she just wanted to be free. She got her wish, in a way. She’s free of responsibilities, free of bills, free of the daily work of caring for someone whose mind is slipping away. She has twelve years to sit in a cell and think about the difference between freedom and selfishness.

As for me, I’m still here. Margaret is still here. Some evenings we sit on the couch, Sinatra low in the background, a glass of iced tea sweating on the table. She leans her head on my shoulder and asks, “Did we have any children?” on the bad days, or “How’s Jenny?” on the middling ones.

“She’s where she needs to be,” I say either way. “And I’m right here.” I kiss her hair, breathe in the faint scent of her shampoo, and stare at the flag magnet across the room until the stripes blur.

I came home from Phoenix to a dark house, a locked door, and a nightmare I still wake up from some nights. I heard my wife’s hands on the other side of that wood and chose to break it open. When the truth about Jennifer came thudding against my chest with the same relentless rhythm, I did the only thing that made sense.

I broke that lock too.

People can call it what they like—justice, punishment, revenge. All I know is this: my wife survived fourteen days in the dark. My daughter planned every single one of those days. I couldn’t give Margaret those hours back, but I could make sure Jenny paid for each one in the only currency the law understands.

In the end, I did exactly what any decent father should do.

I made sure my daughter got exactly what she deserved.

News

My father-in-law cut me out of family photos at our daughter’s first birthday. “Real family only,” he said. My wife didn’t defend me. I left the party early. By the time they needed me to co-sign their mortgage refinance, I was already filing for divorce.

My name echoed through the university arena, sharp against the floodlights, as I walked across that stage expecting—hoping—to see them….

My father-in-law cut me out of family photos at our daughter’s first birthday. “Real family only,” he said. My wife didn’t defend me. I left the party early. By the time they needed me to co-sign their mortgage refinance, I was already filing for divorce.

My name echoed through the university arena, sharp against the floodlights, as I walked across that stage expecting—hoping—to see them….

My father-in-law cut me out of family photos at our daughter’s first birthday. “Real family only,” he said. My wife didn’t defend me. I left the party early. By the time they needed me to co-sign their mortgage refinance, I was already filing for divorce.

My name echoed through the university arena, sharp against the floodlights, as I walked across that stage expecting—hoping—to see them….

I refused to go on the family vacation because my sister brazenly brought her new boyfriend along – my ex-husband who used to abuse me; “If you’re not going, then give the ticket to Mark!” she sneered, and our parents backed her up… that night I quietly did one thing, and the next morning the whole family went pale.

The night my mother’s number lit up my phone for the twenty-ninth time, I was sitting on my tiny city…

my husband laughed as he threw me out of our mansion. “thanks for the $3 million inheritance, darling. i needed it to build my startup. now get out – my new girlfriend needs space.” i smiled and left quietly. he had no idea that before he emptied my account, i had already…

By the time my husband told me to get out, the ice in his whiskey had melted into a lazy…

My father suspended me until I apologized to my sister. I just said, “All right.” The next morning, she smirked until she saw my empty desk and resignation letter. The company lawyer ran in pale. Tell me you didn’t post it. My father’s smile died on the spot.

My father’s smile died the second he saw my empty desk. It was a Thursday morning in late September, the…

End of content

No more pages to load