My daughter gave me a free vacation for her friend’s wedding, and for a few hours I convinced myself it was simply kindness. I was sitting on the balcony of a luxury lakeside resort in northern Michigan, sipping bad hotel coffee from a mug printed with the American flag, watching the stars smear across the black water like spilled silver, when it hit me: the “gift” she’d given me was worth about $3,000. What she was quietly trying to take was closer to $600,000.

That’s what my condo was worth back home. That’s what Grace and I had spent a lifetime earning and protecting. And that was the number printed in tiny, neat type on the line labeled “Estimated Available Equity,” just above the signature she’d pushed toward me with a bright smile and a brand-new pen.

I had my own pen in my breast pocket—the slim navy fountain pen Grace gave me the day I retired from teaching. I’d used it to sign permission slips and detention forms and prom chaperone waivers for decades. I trusted that pen. I did not trust the paper in front of me.

And the moment a stranger’s hand closed around my wrist and he said, “Don’t sign that. It’s not what you think,” I realized my wife had been right about our daughter all along.

Sometimes the real emergency isn’t the one you dial 911 for. It’s the quiet one that walks in smiling and calls you Dad.

My name is Robert Chen. I’m sixty-three years old, and for thirty-seven of those years I taught high school history in a small suburb outside Chicago. Thirty teenagers at a time, five periods a day, nine months a year. If you want to learn how to read people, stand in front of thirty sophomores who all promised they did the homework.

You learn to recognize the glance toward a hidden phone, the fake cough to cover a whispered answer, the twitch in a kid’s jaw when you ask, “Are you sure your mom signed this?” I could spot a forged signature from across the room. I used to joke that I didn’t need a lie detector; I had thirty faces and a clock on the wall.

I thought I was good at reading people. I thought I was good at reading my own family.

I was wrong.

That’s the sentence I kept avoiding, the one that finally landed like a punch: I was wrong about my daughter.

I don’t mean in the ordinary way parents misjudge kids—curfews, college majors, questionable boyfriends. I mean I was wrong about who she became when I wasn’t looking. I was wrong about what she was willing to do with my name, my trust, and my home.

The last person to try to warn me was my wife.

Grace died three years ago from pancreatic cancer. Six months from diagnosis to funeral. Six months of hospital corridors, antiseptic air, French fries eaten cold in the visitors’ lounge. Six months of watching the woman I’d loved for forty years disappear a little more each day, and six months of listening to her say things I did not want to hear.

“Watch Melissa,” she’d whisper, her fingers—always warm before—now cool and thin in mine. “Watch her carefully, Robert. She’s not the person we raised.”

“She’s stressed,” I’d say, smoothing her hair back from her damp forehead. “She drives into the city every day. She’s juggling clients and showings and—”

“I know my daughter,” Grace would murmur, eyes sharp even through the morphine. “I know when she wants something. And I know when she’s hiding something.”

“She’s helping,” I insisted. “She handles the bills when I’m here. She brings us groceries. She’s fine.”

“She’s not fine,” Grace said. “She’s hungry. It’s different.”

I blamed the pain meds. I blamed the fear. I blamed anything except the possibility that Grace was seeing something in Melissa I refused to see.

It’s funny what you’ll call paranoia when the truth is too painful.

The day after we buried Grace, I stood in the kitchen of the old house in Maple Ridge, Illinois, staring at the refrigerator. The same beige GE we’d bought the year Melissa was born, with a faded red-white-and-blue magnet shaped like the United States stuck in the corner. It held up a grocery list Grace never finished and a “World’s Best Teacher” card Melissa made for me in the third grade.

I ran my thumb over that flag magnet and told myself I’d be fine.

We’d done everything right, financially speaking. We’d lived on my teacher’s salary and Grace’s work as an ER nurse, never bought more house than we could afford, never took vacations we couldn’t pay cash for. When other people were refinancing for granite countertops, we were sending an extra hundred dollars a month toward the principal.

Between my pension, our modest investments, and the equity in the house, we were comfortable. Not rich. Secure.

Six months after the funeral, the house felt too big and too haunted. Every room echoed with her absence—the spare bedroom where she kept her quilting supplies, the dining room we only used on Thanksgiving, the tiny bathroom where her hairbrush still sat in the cup.

I sold it.

The realtor told me I could get more if I waited. I didn’t want more. I wanted out. I took a cash offer, signed away the address where we’d watched our daughter take her first steps, and moved into a two-bedroom condo in a lakeside development an hour away, in Oak Harbor.

“New chapter,” Melissa said when she helped me carry the last box in. “Fresh start, Dad.”

She took a picture of me on the balcony, the lake behind me, a little American flag flapping from someone’s boat in the distance. She posted it with the caption: “Helping my widowed dad start his next chapter. Family first.”

The likes and heart emojis rolled in. People love a story about a devoted daughter.

Most Sundays after that, Melissa called. “Did you eat something besides cereal this week? Did you make your doctor’s appointment? Have you met anyone in the building?” Concerned questions, warm voice. The script any counselor would applaud.

“You know you can call me anytime,” she’d say. “You’re not alone, Dad.”

I believed her. Or I believed what I needed to: that my daughter was who I’d always thought she was. It was easier than wondering who else she might be.

Grief makes you soft in all the wrong places.

There’s an odd thing that happens when you get older. People stop asking what you want and start telling you what you deserve.

“You deserve to relax,” they say. “You deserve a break. You deserve a little luxury.”

That’s how the whole thing started—a “deserved” vacation.

It was a Saturday morning in August, humid and bright, the kind of Midwestern summer day when the air feels like wet wool. I was standing in my small kitchen in Oak Harbor, fixing myself what I still called a “proper” breakfast—scrambled eggs, toast, black coffee—when my doorbell rang.

I wasn’t expecting anyone. My social life at that point consisted of nodding at the retired couple down the hall and saying hello to the mail carrier.

When I opened the door, Melissa swept in on a cloud of floral perfume and air-conditioned cool.

“Dad!” she sang out, wrapping her arms around me. “You didn’t answer your phone. I thought you might have fallen asleep in your chair again.”

It was barely nine a.m., but my daughter had already been to a blowout bar, a manicure appointment, and—judging by the branded leggings—a boutique gym class. She wore an athleisure outfit in shades of pale gray and white that probably cost more than my monthly electric bill. Her highlighted hair was pulled into a casual ponytail that had certainly taken a professional stylist twenty minutes to achieve.

“You look great,” I said, and meant it in the way fathers mean it when they’re bewildered by how much their children’s lives cost.

She took in my little condo with quick professional eyes. Realtor eyes. The framed photos on the wall, the second-hand couch, the small TV, the framed print of the Constitution in my hallway I used to point at when students complained about homework.

“You need art,” she said. “And a new couch. And throw pillows. You know I can help you, right? I get discounts through vendors.”

“I like my couch,” I said mildly. “It’s broken in exactly where I sit.”

She rolled her eyes, then clapped her hands once, like she was calling the class to attention.

“Okay. Business. I have the most amazing surprise for you.” She pulled out her phone and started swiping. “Look.”

She held the screen toward me. Photos of a resort filled the display—a wooden lodge nestled in pines, a private lake smooth as glass, Adirondack chairs on a dock, fire pits ringed with soft chairs and golden light. The website banner read: LAKE HARRINGTON LODGE—EXCLUSIVE LAKESIDE RETREATS.

“It’s in northern Michigan,” she said. “Private airstrip, private lake, private everything. My best friend from college, Amanda, is getting married there next month. Weekend wedding. All-inclusive. And I want you to come.”

I blinked. “You want me at your friend’s wedding?”

“It’s not just about the wedding,” she said. “It’s about you getting away. You haven’t left Illinois since Mom—” She stopped, swallowed, recalibrated. “Since everything. You need a change of scenery. And I’m paying for everything. Flights, room, food, the works. My treat.”

“Amanda is okay with that?” I asked, because I could still imagine my own parents inviting random relatives to my wedding without warning.

“Amanda’s thrilled,” Melissa said. “She loves you. She still remembers when you helped her with that history project senior year, remember? Plus, it’s good optics. Family, you know. And Derek and I are doing really well right now.”

She dropped that last part lightly, but something in her tone made my ears twitch. Years of listening for the line between excuse and explanation.

“Really well,” I repeated.

“Really well,” she said. “Derek’s firm just closed a huge deal—like, huge. I’ll bore you with the details later. The point is, we can afford to do something nice for you, for once. Let me do this, Dad. Please. Consider it a thank you.”

“A thank you for what?” I asked.

“For everything,” she said, and to her credit her eyes shone. “For raising me. For working two jobs so I could go to college. For taking extra summer classes so I could have braces. For always being there. You’ve spent your whole life taking care of other people. Let someone take care of you.”

I felt something inside me soften at that. There’s a particular ache that comes with widowerhood, a hollow space where partnership used to sit. You don’t realize how much you miss someone arguing with you about the cable bill until you’re alone with it.

“Mom would want you to go,” Melissa added gently. “She’d want you to be happy.”

There it was. The line you save for the end when you really want something: Mom would want this.

I thought of Grace’s hand in mine, of the way she used to squeeze my fingers when the pain hit hard, the way she’d whisper, “Promise me you’ll live after I’m gone, not just sit.” I thought about the silent condo, the stack of unread books, the evenings I spent watching cable news with the sound low just to prove someone was talking.

“Okay,” I said slowly. “Okay. I’ll go.”

Melissa squealed and threw her arms around my neck. “You will not regret this. I promise.”

Looking back, it’s almost funny how easily promises slide off a tongue that’s already planning something else.

If I’d listened more carefully that day, I might have heard Grace’s voice in my head saying, Be careful which promises you believe.

Instead, I heard only the part of me that wanted to be the kind of father who accepted his daughter’s generosity gracefully.

There’s always a bet at the beginning of a story like this, even if you don’t know you’re making it. Mine was simple: I bet my daughter loved me more than she loved money.

I intended to pay that bet off in gratitude.

She intended to pay it off in equity.

Three weeks later, I stepped out of a small charter plane onto the tarmac of a private strip near Lake Harrington, clutching my carry-on in one hand and my navy fountain pen in the other. Old teacher habits die hard; I still liked having something smooth and solid between my fingers during turbulence.

The resort was exactly as advertised. A long, low main lodge made of pale wood and glass, balconies facing the water, a wide porch wrapped around the front with rocking chairs. The staff greeted me by name when I stepped into the cool lobby, the air scented with pine and expensive laundry detergent.

“Mr. Chen,” the young woman at the front desk said. “Welcome to Lake Harrington Lodge. We’re so happy to have you with us this weekend.”

“Thank you,” I said, suddenly aware of my off-the-rack blazer and shoes I’d buffed myself.

“Your daughter and son-in-law will be arriving in about an hour,” she added. “They arranged an early check-in for you. If you don’t mind signing our standard liability forms and resort agreement, we’ll get you settled in your suite.”

The first paper appeared then—clean white sheets on a clipboard, small print, lines for signatures.

“Just standard stuff,” she said. “Liability for lake activities, spa, that kind of thing. And an acknowledgement that you’ve read our guest policies.”

My hand moved toward the pen she offered, then reflexively went to my own pocket. I pulled out the slim navy fountain pen, the one Grace had wrapped in tissue paper the day I turned sixty and opened at a diner lunch with the whole department.

“For all the things they’ll still make you sign,” she’d joked. “At least make it look dignified.”

Even after three years, the weight of it in my hand felt like her hand on my shoulder.

I scanned the pages in the lobby. Old habits again. There were paragraphs about kayaks and spa treatments, about quiet hours and charges for missing towels. Nothing else. I signed three times, the pen gliding smoothly, my signature steady.

That, I realize now, was the bait. The paper they wanted me to see so I wouldn’t question the paper they’d show me later.

My room overlooked the lake, just like Melissa’s photos. A small terrace with two wooden chairs, a bed big enough for four people, a bathroom with a shower that looked like it belonged in a movie. A bowl of green apples sat on the table next to a welcome card: “We’re so glad you’re here, Mr. Chen. —The Harrington Lodge Team.”

I put my suitcase down. I set my pen on the nightstand. I stood at the glass doors and watched the lake for a long time, the water dark and still under a high blue sky.

I told myself I was lucky. I told myself my daughter was generous. I told myself this was what Grace would have wanted.

It’s astonishing how quietly denial can sound like gratitude.

Melissa and Derek arrived about an hour later, all noise and luggage and the smell of cologne I associated with downtown elevators. Melissa wore a breezy white dress and sunglasses big enough to cover half her face. Derek wore tailored shorts, a golf shirt with a discreet logo, and an expression that said he was used to being the most important man in any room.

“Pops!” Derek said, clapping me on the shoulder. I’d told him, more than once, that I didn’t care for the nickname. I’d told him my students called me Mr. Chen and my friends called me Robert and my wife called me “hey you” when I forgot to take out the trash. I had not, at any point, invited “Pops.”

“Robert,” I corrected automatically.

“Right, right,” he said, grinning. “How’s the room? Good view? Did you try the welcome cookies? They’re insane.”

Melissa kissed my cheek. “Isn’t this place amazing? We wanted you to have the full experience. Anything you want, just charge it to the room. Derek’s got it all handled.”

“We’re so glad you’re here,” Derek added, squeezing my shoulder a little too long. “Family, you know? Family comes first.”

When someone says “family first” at the same time they’re calculating your net worth, it doesn’t mean what you think it does.

That first evening, we sat on the main porch as the sun slid down behind the trees, smearing the lake in orange and pink. Other guests milled around with craft cocktails in their hands, the air humming with polite laughter and soft music from hidden speakers.

Melissa tucked her arm through mine. “So,” she said lightly, “there’s just one tiny thing we need to do tomorrow.”

I felt the first chill then, faint and low, like the whisper of cold air before a storm front.

“What kind of thing?” I asked.

“The resort has a detailed ‘vacation paper’ they require for guests of the wedding party,” she said. “Kind of an extended waiver. Because the whole weekend is technically a private event, not just a stay. Liability, privacy, social media, that sort of thing. You know how it is.”

“No,” I said slowly. “I don’t.”

She laughed. “You’re so old school, Dad. It’s standard. I signed one. Derek signed one. Even Amanda’s parents signed one, and her dad’s a lawyer. It’s boring. I’ll bring it by your room tomorrow morning with coffee. We’ll get it out of the way before the welcome reception.”

“Can’t I just sign whatever I signed at the front desk?” I asked.

“This is separate,” she said quickly. “Wedding stuff. The resort is picky. Trust me, it’s easier to just sign it. You don’t want to be the one who makes a fuss, right?”

Grace’s voice shifted in my memory from a whisper to a murmur. Watch her, Robert. Not her words. Her timing.

“I’ll read it,” I said.

“Of course,” Melissa said, her smile just a little too tight. “You’re you. You read everything. I wouldn’t expect anything else.”

I looked down at my hands. My fountain pen was in my pocket again, the clip catching on the fabric of my shirt every time I moved. I ran my thumb over it and told myself I was in control. I told myself that pen meant something.

That night, after they went back to their own room, I sat on my balcony in the dark with the American flag mug of coffee the resort had left by the in-room machine. Below, the dock lights glowed soft yellow. Somewhere across the lake, someone lit a firepit, tendrils of smoke rising up to mix with the stars.

I thought about Grace. I thought about Melissa. I thought about the way grief can blur your vision, turning red flags into festive banners.

I told myself I’d simply read whatever they gave me. That was all. That was enough.

The first big lie I told myself was that careful reading alone could protect me from people I loved.

The next evening was the welcome reception—a casual gathering on the lawn by the lake, with string lights hung from the trees and waiters circulating with trays of things I couldn’t pronounce. Guests wandered in clusters, laughing and posing for sunset photos, the groom and bride-to-be orbiting like planets around a center I couldn’t see.

I didn’t know many people, so I wandered toward the dock, drawn by the quiet.

That’s where I saw him: a man about my age standing at the far end, hands in the pockets of a faded sport coat, watching the water. He had silver hair cut short, a face seamed by years in the sun, and the solid posture of someone who’d spent a long time wearing a uniform.

“Mind if I stand here?” I asked, stopping a few feet away.

“Free country,” he said without looking over. His accent was pure Midwest.

“Not a fan of weddings?” I tried again.

He huffed something that might have been a laugh. “Not a fan of pretending everything’s fine when it isn’t.”

“Cryptic,” I said.

“Sorry.” He stuck out his hand. “James Whitmore. I’m a friend of the groom’s father.”

“Robert Chen,” I said, taking his hand. “Friend of the bride’s friend.”

His grip was firm, his eyes sharp when they finally met mine. “You’re Melissa’s dad,” he said.

“That obvious?” I asked.

“She has your chin,” he said. Then, after a beat: “And your last name.”

Something in his tone made my teaching instincts sit up straight.

“I do this thing,” I said lightly, “where I ask students what they really mean instead of what they say. So I’m going to do that with you now. What are you actually telling me, Mr. Whitmore?”

For the first time, he looked directly at me, weighing something inside himself.

“Do you mind if we talk somewhere a little more private?” he asked.

We walked down the dock together, away from the lights and laughter. At the end, where the wooden planks met dark water, he stopped and turned toward me.

“Robert,” he said quietly, “what do you know about your son-in-law’s work?”

“He’s a financial adviser,” I said. “Investments, portfolios, that sort of thing. He works with high-net-worth clients in the city. I’ve heard his spiel.”

“Have you invested with him?”

“No,” I said. “I like sleeping at night.”

“Have you signed anything for him?”

The question landed oddly, like a note out of tune.

“No,” I said slowly. “Why?”

James took a breath. “Two years ago, Derek approached me about an exclusive fund his firm was managing. Limited spots. High returns. The usual pitch. I’d just retired. I’d been careful, saved for decades. I should have known better, but he was polished. Confident. Had all the right paperwork, the right jargon. I put in $200,000.”

He paused. The number hung between us like a weight.

“What happened?” I asked, though I already knew the outline. You hear enough of these stories in the teachers’ lounge from colleagues whose brothers-in-law had ideas.

“The fund didn’t exist,” James said. “Not the way he presented it. The documents were technically legal, but the structure was designed so the only person guaranteed returns was Derek. When the ‘market volatility’ hit, guess whose accounts took the hit and whose didn’t?”

“Yours,” I said.

“And at least fourteen other families I know of,” he replied. “Retirees. Widows. People who trusted him because someone they loved vouched for him.”

“Why didn’t you go to the police?” I asked.

“I did,” he said. “For thirty years, I was one of them. FBI—white-collar crime. I can tell you exactly how far a guy like Derek can go without crossing a line on paper. On paper, he disclosed the risks. On paper, we signed. On paper, we agreed. It’s dirty, but it’s clever. The word you’re looking for isn’t ‘illegal,’ it’s ‘predatory.’”

The dock creaked beneath our feet. A loon called once across the lake, lonely and high.

“Why are you telling me this?” I asked.

“Because when I saw your name on the guest list, I recognized it,” he said. “I did a little digging. Your wife passed away three years ago. You sold your house. You moved into a condo you own outright. You’re on a fixed income. You have assets but not backup. And Derek has a pattern, Robert. He targets older relatives who trust him. People who grew up believing if it’s in writing, it must be true.”

I thought of Grace in her hospital bed. Watch Melissa. Watch her carefully.

“My daughter wouldn’t—” I started.

“Your daughter is married to him,” James said gently. “She lives in the life he built on my retirement. She drives a car he paid for with a widow’s savings. I’m not saying she knows everything. I’m saying she knows enough to be comfortable with what he does.”

“That’s not the same as—”

“Tell me something,” James cut in. “Has your daughter been asking more questions about your finances since your wife passed?”

I opened my mouth, then shut it.

“Has she suggested you simplify things?” he asked. “Put the condo in joint names? Give her power of attorney? Let her ‘help’ with your accounts?”

I thought about the phone calls. The gentle questions that had felt like concern. How much do you still owe on the place, Dad? What’s your monthly pension? Do you have a will? We just want to make sure you’re protected.

“Yes,” I said finally.

He nodded like that was all the confirmation he needed.

“I can’t make you believe me,” James said. “But I can ask you one favor: before you sign anything for them this weekend, let me look at it. Any ‘vacation paper,’ any ‘liability waiver,’ anything. Just give me five minutes with it.”

I looked down at the water, dark and deep and utterly indifferent.

“I’ve always been good at spotting lies,” I said. “Thirty-seven years of catching kids who thought they were smarter than the system.”

“How are you at spotting lies when you want them to be true?” he asked softly.

That question, more than anything else he said, slipped under my defenses.

“I’ll let you see whatever they give me,” I said.

“Good,” he replied. “And Robert?”

“Yes?”

“If Derek realizes you’re onto him, he’ll pivot. Guys like him always have a backup plan. So be careful.”

On my way back up the dock, the string lights seemed harsher. The laughter sharper. I watched Derek holding court by the bar, one hand resting lightly on Patricia Yates’s elbow as he leaned in to explain something on his phone. Her husband stood beside her, listening intently.

Hunting, I thought, and shivered, though the air was still warm.

I didn’t sleep much that night. The resort supplied thick duvets and blackout curtains, but nothing for the kind of insomnia that comes when your reality starts to tilt.

I walked circles inside my own head.

I thought about the little things I’d brushed off. Melissa frowning when I told her I’d paid cash for the condo. Her pointing out how much was tied up in “just walls” instead of “working for” me. The way she’d suggested she and Derek could “leverage” my equity into “something more productive.”

“Why let all that money just sit there, Dad?” she’d said once. “You can’t take it with you.”

Following that logic, neither could she.

Around three in the morning, I made myself a cup of weak coffee in the American-flag mug and stepped onto the balcony. The resort was mostly dark, just a few lights glowing down by the dock. The lake reminded me of the blackboard in my old classroom after I’d erased everything: faint ghosts of chalk still clinging to the surface.

If they wanted me to be a confused old man, I thought, maybe that’s who I should let them see.

I pulled my navy fountain pen from my pocket and rolled it between my fingers. Grace had given it to me to sign things with care. That night, I made myself a different kind of promise: I would sign whatever they put in front of me. I would sign it badly. And then I would use every skill I had left to make sure those signatures became the rope they’d tied around their own necks.

The bet shifted that night. I was no longer betting on my daughter’s love. I was betting on my wife’s foresight and my own ability to play dumb.

The next morning, at nine sharp, Melissa knocked on my door carrying a cardboard tray with two lattes and a paper bag that smelled like cinnamon.

“Room service, old man,” she chirped. “Caffeine and carbs and a teeny bit of bureaucracy.”

She set everything down on the coffee table and pulled a folder from her tote bag. It was thicker than anything I’d signed in the lobby.

“Here we go,” she said. “Vacation paper. Don’t worry, I already filled in all your information. You just have to sign and date. They need it before the rehearsal this afternoon.”

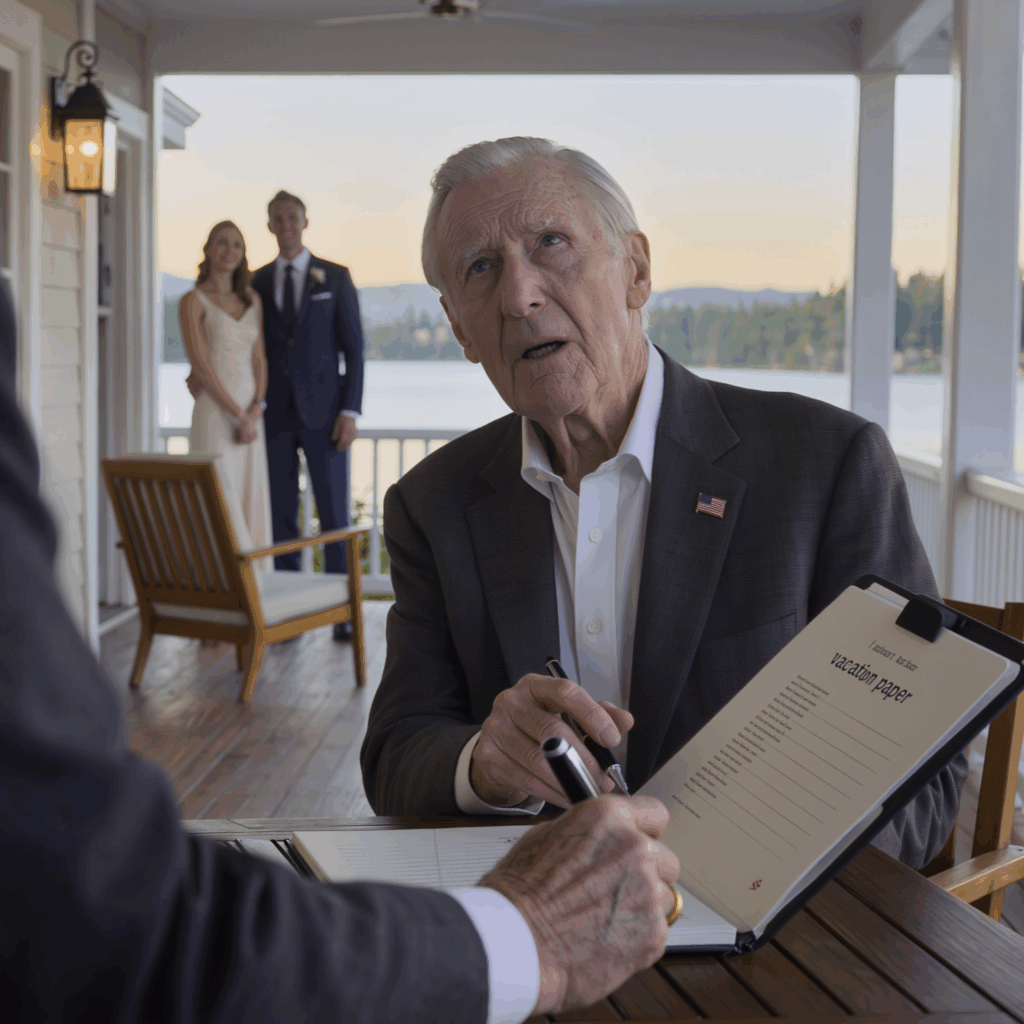

I slipped on my reading glasses and opened the folder.

The first page looked official: the resort logo at the top, then BLOCK CAPITALS: HARRINGTON LODGE GUEST AGREEMENT. The second line read: “This Agreement (the ‘Agreement’) is entered into between HARRINGTON LODGE, hereafter ‘the Resort,’ and ROBERT CHEN, hereafter ‘the Guest.’”

“This looks like something from the resort, not the wedding,” I said mildly.

“It’s all bundled,” Melissa said, tearing into her pastry. “They’re doing, like, their own in-house financing thing. Don’t get bogged down. It’s boring, remember?”

I flipped to the second page. Paragraphs of dense legal text marched down the paper. Words like “security interest” and “lien” began to pop up where I’d expect “kayak” and “check-in.”

“Derek worked it all out with their legal department,” Melissa added. “He’s handling the financial side for the wedding. He said you’d freak out if you saw too much jargon, so just—”

“So just sign,” I finished for her.

She laughed lightly. “Basically. You trust me, right?”

That was the moment, if this were a movie, when everything would go slow-motion and the music would swell. The father’s hand trembling over the page, the daughter’s eyes wide and pleading, the audience whispering, Don’t do it.

Real life is quieter. My hand did tremble, but only a little. My heart did pound, but I’d been taking blood pressure medication long enough to know how to breathe through it.

I read that document. Every line. Every clause. Every reference to a “secured interest” and “primary residence.” It wasn’t a liability waiver. It was a reverse mortgage application. A slick, beautifully designed trap.

In exchange for “enhanced liquidity and financial flexibility,” I would be granting a company I’d never heard of—Mitchell Financial Strategies LLC—a security interest in my condo. The initial payment was listed as $600,000, subject to appraisal. The disbursement schedule would send a portion to a “designated investment vehicle” (Derek’s fund) and the rest to my bank account.

There was a section about automatic withdrawals to cover “fees.” Another about foreclosure procedures if those fees weren’t paid.

My condo wasn’t just my home. It was my last big asset. My safety net. My way to stay independent so Melissa didn’t have to “take care of me” later.

They were trying to take it in a weekend.

“Dad?” Melissa asked, watching me watch the pages. “You okay? You’re awfully quiet.”

“Just tired,” I said. “Old eyes, small print. You know how it is.”

I placed the first page back on top, reached into my pocket, and touched my fountain pen. Then I set it down beside the folder and picked up the black ballpoint she’d laid out instead, the one with the resort logo.

“Where do I sign?” I asked.

Her shoulders dropped an inch in relief. “Here, here, and here.” She tapped three lines with a perfectly manicured nail. “And initial here and here.”

I signed my name on each line: ROBERT CHEN. I made the letters shakier than they needed to be, my hand wobbling just enough to seem unsure.

“Perfect,” she said, gathering the pages swiftly. “I’ll get these to Derek so he can process everything with the resort. We’ll take care of you, Dad. You won’t have to worry about anything.”

As she slid the folder back into her tote, I lifted my phone and snapped a photo of each page, using the reflection in the window to make sure she was still watching the pastry, not me. In each photo, my navy fountain pen lay beside the document like a scale marker in a crime scene.

The pen Grace gave me became my first piece of evidence.

After she left, humming some pop song under her breath, I locked the door and called James.

“We need to talk,” I said when he answered.

“Did you sign?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “And no.”

Within an hour, James was in my room with a woman in her late forties who wore a navy dress and the kind of no-nonsense shoes you only buy if you spend a lot of time standing in courtrooms.

“Robert, this is my sister-in-law, Kathryn,” James said. “She’s here for the wedding, but in real life she’s an attorney. Elder law, fraud, that sort of thing.”

“Nice to meet you,” Kathryn said, shaking my hand with a grip nearly as firm as James’s. “James sent me your photos.”

She sat on the edge of the armchair, glasses perched low on her nose, scrolling through the images slowly.

“This is not a resort waiver,” she said flatly after the third picture. “This is a reverse mortgage arrangement tied to a private investment product your son-in-law manages. It’s loaded with conflicts of interest and written to confuse. Classic.”

“Is it illegal?” I asked.

“That depends,” she said. “Did they explain what it was? Did they tell you it was a reverse mortgage? Did they disclose the risks of tying your primary residence to a single, high-risk investment fund?”

“No,” I said. “They called it a ‘vacation paper.’ A liability waiver.”

“Then we have misrepresentation,” she said. “Possibly fraud. Definitely elder financial abuse. But we have to be strategic.”

“Strategic how?” I asked.

“You signed,” she said. “But they haven’t filed this yet. In fact, they can’t. Not the way they think they can. Did your wife handle the trust documents before she passed?”

I blinked. “What trust documents?”

Kathryn opened her laptop. “I pulled your property records this morning,” she said. “The county database shows an additional document filed about three years ago. A living trust. Your condo isn’t held solely in your name, Robert. It’s in the Chen Family Trust, with a co-trustee.”

“Who?” I asked, my mouth suddenly dry.

“An attorney named Howard Stern,” she replied. “From Chicago. Does that name mean anything to you?”

“Grace went to college with a Howard Stern,” I said slowly. “They stayed in touch. He sent flowers to the hospital when she got sick.”

“According to this,” Kathryn said, turning the screen so I could see, “any attempt to mortgage, sell, or encumber the property requires approval from both trustees: you and Mr. Stern. Without his signature, no reverse mortgage can be recorded. And there’s a clause that mandates an automatic legal review if anyone attempts to file without both signatures.”

My throat closed. The room blurred for a moment.

“So even if Derek tries to file this,” I said, “it won’t go through.”

“It will trigger a legal alarm,” Kathryn said. “And it will give us a paper trail. Your wife was very, very smart.”

I sat back on the bed and pressed my palm over my eyes. The sound that came out of me was somewhere between a laugh and a sob.

“She tried to tell me,” I said. “In those last weeks. She kept saying something was off. I thought she was talking in circles. I thought it was the meds. I told her to rest. I told her Melissa was fine.”

Kathryn closed the laptop gently. “Sometimes the people who love us see things we can’t bear to look at,” she said.

“What do we do now?” I asked.

She folded her hands. “Now we let them think they’ve won. We let Derek believe that in a weekend, with one ‘vacation paper,’ he took a $600,000 bite out of your future. And in the meantime, James and I will be very busy.”

“What are you going to do?” I asked.

“Gather witnesses,” she said. “Connect dots. Talk to other families Derek has worked with. And make sure that when he finally realizes this didn’t go the way he planned, there are federal agents already reading his emails.”

It’s one thing to be the teacher who catches kids cheating on a quiz. It’s another thing entirely to realize you’ve become part of a bigger sting.

That afternoon, I put on my suit, the one I’d worn for Grace’s funeral, and played the part my daughter expected: the slightly bewildered, grateful father along for the ride.

At the rehearsal, I smiled in all the right photos. I told stories about Melissa’s first day of kindergarten, about the time she forgot her lunch and I drove all the way from school to bring it to her. People laughed, dabbed their eyes, told me what a great dad I was.

Derek floated around the room like a shark in a rented tux, just visible below the surface. I watched him corner Patricia and David by the bar again, watched him gesture at his phone, watched Patricia’s face move from skepticism to interest.

After dinner, I excused myself early, claiming “old man bedtime.” Back in my room, I headed straight for the resort’s small business center—a quiet space off the lobby with two computers and a printer.

No one else was there. Most of the guests were still on the lawn, dancing under the string lights.

I sat down, opened a browser, and typed “Mitchell Financial Strategies LLC” into the search bar.

The website was slick. Photos of smiling couples on sailboats. Phrases like “boutique wealth management” and “tailored retirement strategies.” A mission statement that could have been copied from a dozen other firms.

I dug deeper.

SEC filings. State business registrations. Each time I looked up one company, another appeared with a similar name, slightly different address. Mitchell Strategies. MFS Capital. Harrington Ridge Investments. Each formed. Each dissolved. Each lifespan around eighteen months.

For three hours, I followed the trail, clicking from registration numbers to complaint forums to investment message boards. I printed the most damning pieces and stacked them neatly by the keyboard.

Seven separate posts on anonymous forums told the same story: We trusted this guy. We lost everything. He blamed the market and walked away.

Near midnight, a different kind of search result popped up: a scanned PDF of a trust agreement. A familiar name caught my eye: Howard Stern. Another: Grace Elizabeth Chen.

My hands began to shake.

I clicked.

There it was. The Chen Family Trust. Signed and notarized six months before Grace’s diagnosis. Our condo, held in trust. Terms designed to keep it safe. A clause that explicitly cited “the risk of elder financial abuse” as the reason for the co-trustee provision.

Grace hadn’t been paranoid in her last months. She’d been proactive the year before.

I printed the trust. The page emerged warm from the printer, the black ink crisp and solid. I stared at my wife’s signature, at the careful loops of her G and C. I traced them with my fingertip the way I used to trace the curve of her cheek when she fell asleep on the couch.

In a small town outside Chicago, thirty-seven years of teaching had made me a “trusted authority.” Real authority had been quietly gathering behind me all along in the form of a woman who saw what I didn’t.

Back in my room, I called Kathryn again. “I found the trust,” I said when she answered. “Grace did this. She protected the condo.”

“Good,” Kathryn said. “Then tomorrow, we let Derek give his big speech about family and protection. And we answer him with the truth.”

The wedding itself was beautiful. I can admit that, even now.

The ceremony took place at sunset on a wooden platform built out over the lake. The bride wore a simple ivory dress that moved like water. The groom cried when he saw her, the good kind of crying that makes people believe in vows.

I sat in the third row, beside Melissa. Her dress was champagne-colored and perfect. Her smile was perfect. Her nails were perfect.

I watched her slide her hand into Derek’s as they turned toward the crowd after the kiss. For a heartbeat, I saw her as she’d been at five—grinning through a gap-toothed smile, sticky from melting popsicles, clutching my hand at the Fourth of July parade as the marching band passed under a wave of American flags.

Who would have guessed that girl would one day try to turn my home into a financial instrument?

At the reception, I found myself seated at a round table near the center of the room. The place settings gleamed under the chandelier light. Tiny name cards in elegant script marked each plate. Mine simply read “Robert.”

Derek was in his element. He made the rounds, laughing just a bit louder than necessary, clapping other men on the back, kissing elderly aunts on the cheek. When he reached our table, he rested his hand on my shoulder.

“How’s the old man holding up?” he joked. “Not too much excitement?”

“I’ve been in high school assemblies,” I said. “This is nothing.”

He laughed as if I’d meant it as a compliment. “Hey, I just wanted to say thanks again for trusting me this weekend,” he added in a low voice. “You won’t regret it. We’re going to make that equity work for you.”

“I look forward to seeing how,” I said.

It’s strange, speaking two languages at once: what you say out loud and what you mean inside your head. Out loud, I sounded grateful. Inside, every word translated to something else.

The speeches started after dessert. The best man told a story about the groom’s terrible college haircut. The maid of honor cried through three-quarters of her toast. The bride’s father spoke about watching his daughter grow up. People laughed, clinked glasses, dabbed their eyes.

Then Derek took the microphone.

He wasn’t on the program.

“Is this on?” he joked, tapping the mic. “I know, I know. Nobody wants another speech. But I promise I’ll be quick.”

He flashed the room a practiced, self-deprecating smile. He’d probably used the same one when investors asked about fees.

“I just want to say how grateful I am to everyone here,” he said. “Friends, family, colleagues. It means the world that you made the trip. But there’s one person I need to single out.”

He turned toward me and extended his free hand.

“Robert,” he said, “would you stand up for a second?”

Every head at our table swiveled. Melissa nudged my arm.

“Go on,” she whispered. “This is your moment.”

I stood. The room blurred a little under the lights.

“Three years ago, Robert lost his wife, Grace,” Derek said, his voice taking on the warm tone of a commercial for life insurance. “She was an incredible woman. Smart, kind, the glue that held their family together. When she passed, Melissa and I made a promise: we would look after Robert. We would make sure he never had to worry. That’s what family does. Family takes care of family.”

He raised his glass.

“To Robert,” he said. “May you always know you’re loved and protected.”

People around the room echoed the toast. “To Robert!” Glasses clinked. Smiles beamed. More than one person gave me a sympathetic nod, the kind people reserve for fluffy movie fathers who need help.

I sat down, my face hot. I am not a man given to public emotion, but if Kathryn hadn’t stood up when she did, I might have walked out.

“Excuse me,” she said into the pause. “If I could just add something?”

Derek’s smile thinned. “Oh, hey, sure,” he said. “Everybody, this is Kathryn. She’s—”

“I’m the groom’s aunt,” she said. “I’m also an attorney who specializes in protecting older adults from financial harm.”

The room quieted. You could feel the attention tilt.

“Derek is absolutely right about one thing,” she continued. “Family should take care of family. Which is why what happened this weekend is so troubling.”

She looked straight at Derek.

“Yesterday, Derek presented Robert with a document he described as a ‘vacation paper’ and a liability waiver,” she said. “In reality, it was a reverse mortgage agreement that would have allowed Derek’s company to gain control of Robert’s $600,000 in home equity. Without Robert’s informed consent. Without disclosing the risks. And with the intent to funnel those funds into an investment product Derek controls.”

Someone gasped. A waiter paused mid-step, tray hovering.

“The only reason that didn’t happen,” Kathryn went on, “is because Robert read the document. And because his late wife, Grace, had the foresight to place their home in a trust that requires a second signature for any such transaction. A signature Derek did not know he needed.”

My heart hammered, not with fear but with a wild, unfamiliar surge of vindication. Grace’s signature, from three years ago, was rewriting the script standing in front of me.

“In addition,” Kathryn said, “I’ve spoken in the last twenty-four hours with three other families here tonight. The Whitmores, the Pattersons, and the Yateses. All were approached by Derek to invest in his fund. Two families have already lost hundreds of thousands of dollars. One was days away from signing.

“We’ve compiled their statements and the documentation Robert found. Federal authorities and the state securities division have also been notified. In fact, I believe some of them are here now.”

Right on cue, two men in dark suits at the back of the room stepped forward, badges in hand.

For a heartbeat, everything was frozen. The bride’s fork hovered halfway to her mouth. The band stopped playing midsong. Someone dropped a champagne flute. Glass shattered against the floor.

Then the room erupted.

People started talking, loudly and all at once. Chairs scraped. A woman began to cry. The bride’s mother put a hand to her chest like she’d been shot.

Derek bolted.

He dropped his glass and ran, actually ran, toward the side exit. For a second, everyone just watched, stunned. Then James moved. For a man his age, he was quick. He intercepted Derek near the door, pivoted, and brought him down in a move that was part high-school wrestling, part federal training.

By the time the agents reached them, Derek was facedown on the polished floor, James’s knee in his back.

“Do not resist,” one of the agents said.

“I’ll call my lawyer,” Derek shouted, his voice cracking. “This is a misunderstanding. You can’t—”

“Yes,” the agent said calmly. “We can.”

They cuffed him right there on the reception hall floor, in front of the ice sculpture and the three-tiered cake and every person he’d been planning to charm that evening.

It would have been satisfying if it hadn’t been so sad.

Through it all, Melissa stood in stunned silence, her hands pressed to her mouth, eyes fixed on Derek as if watching him might somehow rewind the last five minutes.

When they finally led him out, she turned to me.

“Dad,” she said, her voice thin. “I didn’t know. I swear I didn’t know what he was doing.”

“Melissa,” I said quietly, “you brought me the papers.”

“I thought it was a refinance,” she said. “I thought it would help with your expenses. Derek said—”

“Don’t,” I said. “Don’t tell me what Derek said. Tell me what you knew.”

She swallowed. “I knew…it was something with the house. I knew it would free up money for you. For us. He said you were sitting on all that equity, and you weren’t even using it. He said we could get you more comfortable. Maybe get you private care if you ever needed it. I thought it was a good thing.”

“You knew it would give him control,” I said. “You knew it would tie my home to his fund.”

She hesitated just long enough.

“I thought it was safe,” she whispered.

“You watched me sign,” I said. “You watched me put my name on something you didn’t understand. And you didn’t stop me.”

“I trusted my husband,” she said. “Is that a crime now?”

“No,” I said softly. “But letting him prey on your father is.”

Her eyes filled with tears. “I’m your daughter.”

I looked at this woman in a champagne dress and thought about the little girl with sticky hands at the Fourth of July parade. Somewhere between those two images, something had broken.

“The girl I raised,” I said, “never would have let this happen. I don’t know who you are.”

She flinched like I’d slapped her.

That night, after the chaos died down and the guests scattered in stunned little clusters, there was a knock on my hotel room door.

“Dad, please.” Melissa’s voice, small and raw. “Open the door. I need to talk to you.”

I almost didn’t. I almost let her stand there with the weight of her choices.

In the end, I opened it.

She looked terrible. Makeup smeared, hair falling out of its careful updo, shoulders slumped. For the first time in years, she looked like the kid who used to show up at our bedroom door after a nightmare, clutching her stuffed bear by one ear.

“Derek’s been arrested,” she said unnecessarily.

“I was there,” I said.

“They’re saying he could get three to five years,” she went on. “His lawyer says maybe less if he cooperates. But everything’s frozen. Our accounts, the condo, the cars…everything. I don’t know what I’m supposed to do.”

“You’re a licensed realtor,” I said. “You know how to work. You know how to live on commission. You’ll find a way.”

“I can’t do it alone,” she said. “I need help. Mom would have helped me.”

“Your mother,” I said, “saw this coming. She set up a trust to protect me. From this. From you.”

“That’s not fair,” she snapped, some of her old sharpness flashing through. “I’m not a villain. I made mistakes. I trusted the wrong person. But I didn’t sit there scheming how to hurt you.”

“You brought me here,” I said. “You put papers in front of me you didn’t understand. You asked me to trust you. You watched me sign away, in your mind, my home. That’s not a mistake, Melissa. That’s a choice. A series of them.”

“What do you want me to say?” she demanded. “That I’m sorry? Fine. I’m sorry. I’m sorry I didn’t read the fine print. I’m sorry I believed my husband. I’m sorry I tried to make sure you had more money instead of less.”

“You’re sorry it blew up,” I said. “You’re sorry you lost your safety net. That’s not the same as being sorry for what you were willing to risk.”

Tears spilled over. They looked real. Maybe they were.

“I’m your daughter,” she said again, as if repetition could make it a shield. “You’re supposed to help me.”

“I helped you for thirty-plus years,” I said. “College. Rent. Co-signing the loan on your first car. Babysitting whenever you needed. I have paid my share. What I am not going to do is pay for you to learn that actions have consequences.”

Her face hardened. Something in her shut like a door.

“Fine,” she said. “If that’s how you want it.”

“It’s not what I want,” I said. “It’s what is.”

She turned and walked down the hallway, the click of her heels echoing off the hotel walls.

I closed the door.

I did not cry. Those tears had been spent at a printer hours before, with Grace’s signature under my fingers.

The next morning, James drove me back to Oak Harbor. The resort had offered to arrange transportation, to “make things right” with distraught guests. I wanted out of there in a car with someone who knew how it felt to have your life knocked off kilter without warning.

We drove mostly in silence, the highway sliding by in long gray strips.

“You okay?” James asked as we turned into my condo complex.

“I don’t know what that means anymore,” I said. “But I’m upright. That’s a start.”

At home, I unlocked my door and stepped into the quiet. The same second-hand couch. The same framed photos. The same American flag magnet on the fridge holding up the faded grocery list Grace started the week before she went into the hospital.

The condo felt different. Or maybe I did. Once you see how close you came to losing something, it’s hard to look at it the same way.

“Can I give you a piece of advice?” James asked at the doorway.

“From a man who lost two hundred thousand dollars to my son-in-law?” I said. “Please.”

“Don’t let this turn you into someone paranoid,” he said. “But don’t pretend it didn’t happen, either. Trust, but verify. Love, but protect yourself. You’re allowed to do both.”

“Grace would like you,” I said.

“She sounded like a smart woman,” he replied.

After he left, I went to my bedroom closet and pulled down the box I’d shoved to the back three years ago.

Grace’s things. Her jewelry. Her favorite blue scarf. The journal she kept during her last year.

I hadn’t been able to open it before. Reading her last months felt like trespassing on a grief I hadn’t finished yet.

Now, I lifted the journal from the box and carried it to the kitchen table. I set my navy fountain pen beside it, the one that had sat next to the scam papers on my hotel coffee table, a silent witness.

The first entries were simple. Notes about patients. Observations about coworkers. A list titled “Things To Do Before I Can’t Anymore.” On that list, in her neat nurse’s handwriting, were items like “Visit the lake” and “See Melissa’s new condo” and “Find a good lawyer for the trust.”

As the pages went on, the tone changed. She started writing about Melissa more.

“Melissa asked about our retirement accounts again today,” she wrote on one page. “She framed it as concern. I’m not sure it is. Something in the way she talks about ‘unlocking value’ makes my skin crawl.”

On another: “Told Robert we should talk to Howard about putting the new condo in a trust. He brushed me off. He hates paperwork. I’ll call Howard myself.”

There were softer entries, too. Memories of our early years. The way Melissa used to fall asleep on my chest watching Sinatra movies on Sunday afternoons. The smell of chalk dust in my hair when I came home from school.

Near the end, the writing grew shaky.

“Robert will be mad when he finds out about the trust,” she wrote. “He’ll think I didn’t trust Melissa. But I know what I see. Our daughter is turning money into a god. I can’t stop that. But I can shield him from the worst of it. Sometimes loving someone means protecting them from the people they love.”

The last entry was three days before she died.

“I hope he forgives me,” she wrote. “I hope he understands. I hope he survives what’s coming. If he’s reading this, it means he did. If he’s reading this, tell him I love him.”

Ink bled where a tear had fallen on the page and dried.

I closed the journal and rested both hands on the cover. Then I picked up my navy fountain pen and laid it across the top, like I used to lay it across a graded essay when I’d written, “See me after class” at the top.

Grace had graded my life more accurately than I had. She’d given me a passing mark when I thought I was failing and a warning when I thought everything was fine.

Three weeks later, I sat on a hard wooden bench in a federal courtroom in downtown Chicago, wearing the same suit I’d worn to the wedding and the funeral, my navy pen in my breast pocket like a tiny blue shield.

Derek sat at the defense table in a cheap suit that tried to look expensive. He’d lost weight. His hair was less perfect. But his expression was the same—a mix of charm and wounded pride.

Melissa sat in the back row, on the opposite side of the aisle from me. She wore a plain dress, no jewelry. Her hair was pulled back in a low ponytail. She looked like someone who wanted desperately to be mistaken for a victim.

When they called my name, I walked to the witness stand, placed my hand on a Bible, and swore to tell the truth.

The prosecutor asked me to describe, in my own words, what had happened that weekend at Lake Harrington Lodge.

I told them about the first “vacation paper.” About James’s warning on the dock. About the second set of documents. About my daughter’s bright smile and the way she’d said, “You trust me, right?” About signing my name in shaky letters. About discovering the trust. About my wife’s foresight.

I spoke for forty minutes.

Derek’s attorney tried to imply I was confused. That I’d misunderstood. That my age and grief made me misremember.

“Mr. Chen,” he said, “you’re sixty-three years old, correct?”

“Yes,” I said.

“You’ve been through a lot in the last few years,” he added. “Your wife’s illness, the sale of your home, your retirement. Would you say your memory is as sharp as it was when you were, say, forty?”

“Objection,” the prosecutor said. “Relevance.”

“I’ll allow it,” the judge said. “But get to the point, counselor.”

“I’m simply establishing context, Your Honor,” the defense attorney said smoothly. He turned back to me. “Mr. Chen, do you sometimes forget things? Misplace your keys? Struggle with details?”

“Sometimes,” I said. “I’m human.”

“And yet you’re telling us you recall every line of a document you glanced at one morning at a resort?”

“I didn’t glance,” I said. “I read. Every line. Because that’s what I’ve done for thirty-seven years as a teacher and for sixty-three years as someone who doesn’t like being fooled.”

The prosecutor stepped forward.

“Mr. Chen,” she said, “how many essays do you estimate you’ve read and graded over the course of your career?”

“Tens of thousands,” I said.

“And in that time,” she continued, “did you develop an ability to tell when someone was trying to get away with something in writing?”

A ripple of quiet laughter moved through the courtroom.

“Yes,” I said. “If a student tried to slip something past me in an essay, I saw it.”

“And did that habit continue into your retirement?” she asked. “Do you still read what’s in front of you carefully before signing your name?”

“Always,” I said.

“That’s all,” she said.

In the end, the judge sentenced Derek to four years in federal prison, with the possibility of release in three for good behavior. He was ordered to pay restitution—a number that made the courtroom murmur.

He turned once in his seat to look at us—the rows of people whose stories had unraveled his. His gaze slid past me, landed on Melissa. For a second, their eyes met. Something passed between them, too quick for me to read.

Melissa left before the sentencing was fully read. I watched her slip out the back, her shoulders rigid, her steps quick.

She did not look back.

People sometimes ask me, in quiet conversations over coffee at the diner or after church, if I’ve heard from her since.

I haven’t.

Last I heard, through a mutual acquaintance, she moved to the West Coast. New city. New brokerage. New start. Maybe she tells people she’s “estranged” from her father. Maybe she tells them I chose money over family. Maybe she doesn’t mention me at all.

I don’t know.

What I do know is this: I keep the American flag magnet on my fridge. It holds up a new list now—things I need at the grocery store, appointments I don’t want to forget, the phone number of the SEC investigator who handled Derek’s case. It also holds a small photo—Grace on the dock of some other lake, years ago, wearing a faded Cubs cap and smiling into the sun.

I read her journal on hard days. I sit at my kitchen table with a cup of coffee in my hand and my navy fountain pen lying across the open pages, and I listen to her voice in my head.

Trust, but verify.

Love, but protect yourself.

Family, but not at the cost of your own home, your own future, your own sense of right and wrong.

I was wrong about my daughter. That’s a hard sentence to write, let alone live with. But being wrong doesn’t mean I have to stay blind.

Grace knew that. She saw past the Instagram captions and the matching cars to the hunger underneath. She protected me when I didn’t want to protect myself.

The greatest gift she gave me wasn’t the condo or the trust or the fountain pen I still carry. It was the permission to let go of a story that was hurting me.

We raise children, and we tell ourselves stories about who they are—kind, loyal, honest. Sometimes those stories stay true. Sometimes they don’t. The hardest part isn’t admitting they changed. It’s admitting we missed it.

I can’t fix what Melissa chose. I can’t rewrite the weekend at the lake or the years that led up to it.

What I can do is sit here, on my modest balcony overlooking a small Illinois lake, watching an ordinary sunset paint the water in colors no resort photographer would bother to capture, and be grateful.

Grateful that my wife was as stubborn as she was loving. Grateful that a stranger grabbed my hand and said, “It’s not what you think.” Grateful that my blue fountain pen ended up on the right side of the story.

I still believe in trust. I still believe in family. I still believe in giving people chances.

I just no longer believe those things require me to sign away my home—on paper or in my heart—for somebody else’s idea of a good deal.

News

My father-in-law cut me out of family photos at our daughter’s first birthday. “Real family only,” he said. My wife didn’t defend me. I left the party early. By the time they needed me to co-sign their mortgage refinance, I was already filing for divorce.

My name echoed through the university arena, sharp against the floodlights, as I walked across that stage expecting—hoping—to see them….

My father-in-law cut me out of family photos at our daughter’s first birthday. “Real family only,” he said. My wife didn’t defend me. I left the party early. By the time they needed me to co-sign their mortgage refinance, I was already filing for divorce.

My name echoed through the university arena, sharp against the floodlights, as I walked across that stage expecting—hoping—to see them….

My father-in-law cut me out of family photos at our daughter’s first birthday. “Real family only,” he said. My wife didn’t defend me. I left the party early. By the time they needed me to co-sign their mortgage refinance, I was already filing for divorce.

My name echoed through the university arena, sharp against the floodlights, as I walked across that stage expecting—hoping—to see them….

I refused to go on the family vacation because my sister brazenly brought her new boyfriend along – my ex-husband who used to abuse me; “If you’re not going, then give the ticket to Mark!” she sneered, and our parents backed her up… that night I quietly did one thing, and the next morning the whole family went pale.

The night my mother’s number lit up my phone for the twenty-ninth time, I was sitting on my tiny city…

my husband laughed as he threw me out of our mansion. “thanks for the $3 million inheritance, darling. i needed it to build my startup. now get out – my new girlfriend needs space.” i smiled and left quietly. he had no idea that before he emptied my account, i had already…

By the time my husband told me to get out, the ice in his whiskey had melted into a lazy…

My father suspended me until I apologized to my sister. I just said, “All right.” The next morning, she smirked until she saw my empty desk and resignation letter. The company lawyer ran in pale. Tell me you didn’t post it. My father’s smile died on the spot.

My father’s smile died the second he saw my empty desk. It was a Thursday morning in late September, the…

End of content

No more pages to load