My stepmother had one hand on the ICU door and the other on my chest when the security guards came around the corner. Behind her, through the narrow pane of glass, I could see a flash of my father’s hospital bed and the steady green pulse of a heart monitor. In front of me, fluorescent lights hummed, the floor smelled like lemon disinfectant, and my car keys dug into my palm because I was squeezing them so hard. Eight hours earlier I’d been on I‑84 with a chipped white coffee mug in my cup holder—the one with the faded American flag on the side Dad used every Sunday when we talked on the phone. Now I was being treated like a stranger in a building where my father might not live through the night.

“Family only,” Diane said, her red nails biting into the doorframe like talons. “You’re not his real son.”

That was the sentence that split my life into before and after.

I’d driven eight hours straight from Portland to Mercy General Hospital. No real meals, just two gas station hot dogs I regretted immediately and enough burnt coffee to kill a horse. The last hour had been all adrenaline and highway lines blurring together while my phone’s navigation calmly told me where to turn like this was just another trip. The chipped flag mug rattled in the holder every time I hit a bump, sloshing lukewarm coffee onto the plastic. I’d grabbed it on instinct when I left my apartment, the way other people grabbed house keys or their wallet. It smelled faintly like hazelnut creamer and home.

The nurse’s voice from that morning still echoed in my head as I stood there in the ICU hallway, blocked by the woman who’d married my father eight years ago and spent at least six of them pretending I was a temporary inconvenience.

“Massive heart attack,” she’d said over the phone. “You should come now.”

Come now meant come say goodbye. Every part of me had understood that even if her professional tone never used those words.

“Diane, please.” My voice cracked, my throat raw from crying in the car somewhere outside Boise. “I need to see him.”

“You’ve done enough,” she snapped, stepping fully into the doorway to block my view. “We’ve moved on, Marcus. We built a new family. A real family.”

Behind her shoulder, through that thin gap between her body and the frame, I caught a clearer glimpse of my father’s room. Machines beeped in harsh, rhythmic patterns that sounded like countdown timers, not lifelines. Clear plastic tubes snaked from IV poles into his arms. Another tube ran to an oxygen mask fogging faintly with each too‑shallow breath. Electrodes dotted his bare chest like question marks, each one wired to a monitor tracking every struggling heartbeat.

His face was gray against the white pillow. Not pale—gray. Sunken. Older by a decade than the last time I’d seen him six months earlier at Easter, when he’d grilled hot dogs in the backyard wearing an apron that said KISS THE COOK in big red letters. That man had been solid, laughing, complaining about the Mariners’ pitching. This man looked like someone had pulled the plug on his color.

“I’m his son,” I said. It came out smaller than I meant, like I was twelve again and trying to convince a referee that the other kid fouled me.

Diane’s lips curled when she said my mother’s name. “You’re Helen’s son,” she corrected, turning my mother—his first wife—into an insult. “You’re the mistake he made before he met me.”

The ICU corridor smelled like bleach, old coffee, and that particular staleness of recycled air that never quite goes away in American hospitals. A nurse pushed a medication cart past us, glanced at the confrontation, made brief eye contact with me, then glued her gaze to the chart in her hands like it contained all the answers. Nobody wanted to get involved.

“He raised me,” I said, trying to keep my voice steady. “For twenty‑three years. That makes me his son. That makes me family.”

“Biology makes you his son,” Diane shot back. “Love makes you nothing.”

She pulled out her phone—latest iPhone, rose‑gold case, lock screen photo of her and Dad on some beach in Mexico, his skin tanned, her smile wide and practiced. Her carefully curated life, all filtered and cropped, with no room in the frame for me.

Her thumbs flew over the screen.

“Yes, ICU wing, third floor, Room 347,” she said. “Someone’s harassing me. I need security up here immediately.”

It was surreal, standing in that hallway, realizing the woman who shared my father’s last name was calling in reinforcements on me when all I wanted was five minutes by his bed. This was supposed to be hard because of his health, not because of politics.

But in my family, politics always found a way to sneak in.

Two years earlier, I’d left our hometown in eastern Washington for a job in Portland—software development for environmental monitoring systems. Sensors in rivers, machine‑learning models, dashboards that showed water quality changes in real time. Nerd heaven. Good pay. The kind of opportunity you don’t turn down when you’ve spent your twenties watching friends flip burgers and wonder what happened to their dreams.

Dad had been proud. Proud enough that his voice shook a little when he’d said, “You do it, Marcus. Don’t you dare stay here for me. I’ll be fine.”

Diane had called it abandonment.

“You’re choosing your career over family,” she’d said during my last Sunday dinner before I left. The one where Dad charred the burgers because he kept walking inside to refill our iced tea and hide the way his eyes kept watering. “Running away from the people who love you.”

That wasn’t fair. I’d invited them to Portland a dozen times. Sent plane tickets twice—actual paid‑for round‑trip tickets, two passengers, coach from Spokane to PDX, total cost just over 720 dollars each time, which was a lot to me back then. Diane always had an excuse. Headaches. Dad was tired. They had other commitments. It wasn’t a good time. Always something.

But she made sure everyone knew I was the one who’d left.

At Thanksgiving, Dad’s brother Tom had started making comments. “Nice of you to show up, Marcus. Thought maybe you’d forgotten where we live.” Dad’s old friends from Rotary would ask, “How’s your son in Portland? Does he ever visit?” And Diane, with that little sigh she’d perfected, would say, “Oh, he’s busy. Career man. You know how it is.”

Piece by piece, she’d constructed a narrative: the ungrateful son who abandoned his father, the selfish kid who chose money over family, the one who didn’t care enough to come home. And now she was using that story as a weapon to keep me out of his hospital room.

I heard the guards before I saw them. Heavy footfalls, radios crackling softly, the faint jingle of keys clipped to belts. Two men in navy uniforms turned the corner at the end of the hall, moving with the alert, economical pace that screamed prior service.

“That’s him,” Diane said, pointing straight at me, her voice pitching up like she was the one in danger. “He’s been threatening me, screaming at me, following me. I’m afraid for my safety.”

The taller guard held up both hands in a calming gesture. “Ma’am, we need you to take a breath,” he said. I appreciated that for about half a second—right up until he turned to me. “Sir, we’re going to need you to leave this area.”

“I just want to see my father,” I said. My hands were shaking so badly I shoved them into my pockets. “Five minutes. That’s all I’m asking.”

The shorter guard, stocky with a shaved head and kind eyes that said he hated this part of the job, glanced at Diane. “Is this man related to the patient?”

“Stepson,” Diane said quickly, like she’d practiced the word until it lost all syllables but the sting. “Not blood, not welcome. His father specifically said he doesn’t want to see him. It’s too stressful. The doctor said no stress.”

Lies. All lies. But in that moment I had no way to prove any of it.

“Sir,” the taller guard said, “we don’t make these decisions. Family does. We just enforce policy. We’re going to escort you downstairs.”

“I drove eight hours,” I said, and hated how desperate it sounded, how thin. “Please. He’s my dad.”

“Sir,” the shorter one repeated softly, already taking my arm with a grip that was gentle but unyielding. “Please come with us.”

They walked me toward the elevator, one on each side, professional and polite, like I was a slightly tipsy fan being led out of a baseball stadium instead of a son being walked away from his father’s possible last hours. We passed nurses who suddenly found very urgent reasons to study their clipboards. Patients in wheelchairs pretended not to see, their eyes fixed on some point in the distance.

Diane stayed at the ICU doorway, arms crossed, chin up. Victorious. She smiled just as the elevator doors slid shut and my reflection bloomed in the brushed steel: red‑rimmed eyes, wrinkled shirt, eight hours of highway dust on my jeans, defeat written in every slumped line of my shoulders.

That was the moment I realized this wasn’t just about one visit.

They escorted me through the lobby, past the gift shop selling teddy bears holding hearts that said FEEL BETTER SOON and balloons printed with cartoon suns. Past the cafeteria, where the smell of burnt coffee hit me like a wave and my stomach twisted. Through the automatic doors that whooshed open like the building itself was exhaling me.

“Don’t come back upstairs, sir,” the tall guard said—not unkindly, but firmly. “Hospital policy says if family restricts visitors for a critical patient, we have to abide by that. We can’t have disturbances in the ICU.”

“I understand,” I lied. Because what else could I say? I watched them walk back inside, radios crackling, leaving me alone in the parking lot as the sun started to dip low, turning the hospital windows into panels of orange and gold.

It was a beautiful evening. It felt obscene.

My car was somewhere in Section C of the sprawling visitor lot. I’d parked on autopilot, mind full of sirens and worst‑case scenarios, and now I couldn’t remember exactly where it was. I wandered for a minute between rows of pickups and sedans, past a minivan with a faded US flag magnet peeling off the bumper. A little plastic rectangle flapping in the breeze, barely hanging on.

When I finally spotted my gray Subaru, the chipped white mug with the faded flag was still in the cup holder, a ring of dried coffee crusted around the rim. I opened the door and sat hard, keys still clenched in my fist. My phone buzzed in my pocket.

A text from my aunt Linda—Dad’s sister‑in‑law.

“Diane says you showed up and caused a scene. Is that true?”

I stared at the message until the words blurred, then locked the screen and dropped the phone on the passenger seat next to the mug. For a second, all I could do was sit and listen to my own breathing and the faint whoosh of cars on the road beyond the parking lot.

Then I remembered something.

Six months earlier—April—Dad’s lawyer had called me. I’d been at my kitchen table in Portland with that same chipped flag mug next to my laptop, an email about watershed data open on the screen.

“Marcus, this is Dennis Kowalski,” the man had said. He’d been my father’s estate attorney for twenty years, ever since Mom died. “Your father’s updating some paperwork. He’d like to put a few things in writing. Emergency contacts, medical directives. Can I email you some forms?”

“Sure,” I’d said, thinking it was just more of Dad’s newfound obsession with being prepared. He’d started keeping a go‑bag by the front door after a windstorm knocked out power for three days. “He okay?”

“Quite all right,” Dennis had said, cheerful. “Just wants his ducks in a row. Smart man.”

Later that night, Dad and I had our usual Sunday call. We had a ritual: I made coffee in the chipped flag mug, he made tea in the same chipped flag mug’s twin at his house—he’d bought a set of two on clearance at Walmart years ago. We’d both sit at our respective kitchen tables, several hundred miles apart, and pretend we were across from each other.

“I’m putting you down as my medical power of attorney,” he’d said that night, his voice strong, certain. “You’re the only one I trust to make the right call if something happens.”

“I think Diane should be the one,” I’d protested. “She’s your wife. She’s there.”

“Diane loves me,” he’d said carefully. “But she doesn’t always make decisions based on what’s best. She makes them based on what feels right in the moment. If something happens, I need someone who’ll listen to the doctors and follow my wishes, even if it’s hard. That’s you, Marcus. You got your mother’s brain and my stubborn streak. It’s a good combination for this.”

I’d laughed, uncomfortable. “You’re not going anywhere for a long time, old man.”

“Humor me,” he’d replied. “Consider it one more thing I can stop worrying about.”

Now, sitting in that parking lot, the memory slammed back into me with the clarity of a high‑def replay. My hands suddenly weren’t just shaking from anger—they were moving.

I picked up my phone, scrolling back through six months of email. Past work threads, apartment building notices, a spam message about winning a $5,000 prepaid card. And then I saw it:

Subject line: DAVID CHEN – MEDICAL POA AND ADVANCED DIRECTIVES.

I tapped it open. There it was: a PDF attachment I’d opened once, scanned, and filed mentally under “scary grown‑up stuff I’ll deal with later.”

Now “later” was here.

I downloaded the document and opened it. Legal language filled the screen. Notarized signatures. My father’s name, my name. One section in bold almost glowed:

“Medical Power of Attorney: I, David Lawrence Chen, designate my son, Marcus James Chen, as my primary health care agent, authorized to make all medical decisions on my behalf in the event I am unable to do so.”

April 12. Six months ago. Dennis’s signature. A paralegal witness named Jennifer Martinez. A notary stamp from Spokane County.

My heart hammered against my ribs like it was trying to punch its way out.

“If you abandoned him, why would he trust you with this?” a small, vicious part of my brain asked.

“You know why,” another part answered. “Because you didn’t abandon him.”

I backed out of the email long enough to pull up my call log. Sundays, 7 p.m., for the last two years. One hundred and four calls in a row. I counted them twice, finger dragging down the screen. One hundred and four tiny lines of proof that I hadn’t gone anywhere, even if Diane pretended otherwise.

One hundred and four Sunday nights of talking about everything and nothing—about the Mariners and my code, his back pain and my rent, the way the light hit Mount Hood at sunset and the new American flag magnet he’d picked up at the hardware store because the old one faded.

One hundred and four reminders that I was his son, in every way that mattered.

I exhaled once, long and shaky, then tapped the phone icon.

“Mercy General Hospital,” an automated voice said. “If this is a medical emergency, please hang up and dial 911. For admissions, press one. For administration, press three.”

I pressed three.

“Administration, this is Patricia Odum,” a brisk voice answered after five rings.

“Ms. Odum,” I said, surprised my voice came out steady. “My name is Marcus Chen. My father, David Chen, is a patient in your ICU. I’m being denied access by his wife, but I hold his medical power of attorney. The documents were filed with the hospital in April.”

There was a beat of silence, then rapid typing.

“Can you send me verification of that, Mr. Chen?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. My fingers were already moving. I forwarded the email with the attachment to the address she gave me, double‑checked it, hit send, and then stared at the tiny spinning circle that meant the message was leaving my phone and heading toward someone who might actually do something.

In the few seconds it took, I imagined every worst‑case scenario. What if Dad had changed his mind and revoked the paperwork? What if Diane had convinced him to sign new forms last week? What if the hospital had somehow lost the documents? What if I was clinging to a piece of digital paper that meant nothing?

“Mr. Chen,” Patricia said, bringing me back. “I’m looking at your father’s file now.” More typing. A long pause. “You’re correct. You’re listed as David Chen’s medical power of attorney. These forms were uploaded to our system on April 14.”

“My father’s wife just had me physically escorted out by security,” I said, the words tumbling out faster now. “She told them I was harassing her. They told me I couldn’t come back upstairs because ‘family said no visitors.’”

The typing stopped. When Patricia spoke again, her voice had shifted from neutral to something cold and precise.

“She did what?”

“She told them I wasn’t family,” I said. “She said my father doesn’t want to see me. None of that is true. We spoke every Sunday. He’s the one who asked me to be his medical power of attorney.”

Another silence. I could practically hear her brain switching gears, calculating risks and policies and potential lawsuits.

“That was unauthorized,” she said finally. “The medical power of attorney supersedes spousal authority in matters of health care decisions. If you’re the designated agent, you have full legal access to the patient. Where are you right now, Mr. Chen?”

“In the visitor parking lot. Section C, row… I don’t even know. Somewhere near the exit,” I said.

“Come back to the main entrance immediately,” she said. “I’ll meet you there.”

For the first time since I’d walked into the ICU, someone sounded like they believed I belonged.

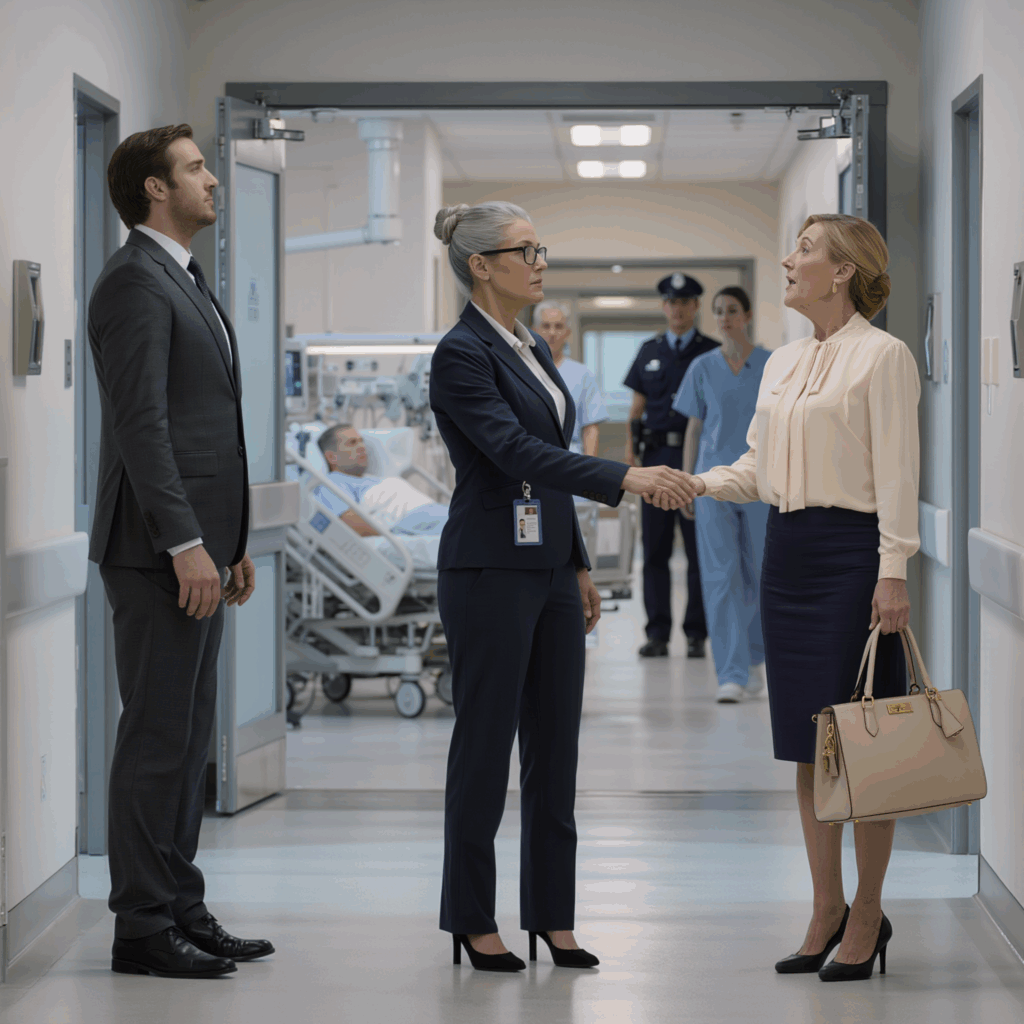

Five minutes later, the automatic doors at the main entrance whooshed open again. A woman in her mid‑fifties stood just inside, gray hair pulled back in a no‑nonsense bun, navy blazer over a white blouse, hospital ID clipped neatly to her lapel. A tiny enamel US flag pin glinted above her badge.

“Mr. Chen?” she asked.

“That’s me,” I said.

She looked me over quickly—the wrinkled clothes, the eight‑hour drive written in road dust on my jeans, the red eyes I couldn’t hide. Her expression softened almost imperceptibly.

“I’m Patricia Odum, the hospital administrator on duty,” she said. “Please, follow me.”

We walked past the information desk, past a security station where one of the guards who’d escorted me out earlier glanced up, did a double take, and wisely said nothing. Patricia’s heels clicked against the tile with a rhythm that matched my heartbeat.

“How long did you drive?” she asked as we stepped into the elevator.

“Eight hours,” I said. “From Portland.”

She nodded once, like she was filing that away.

“You said you spoke with your father regularly?”

“Every Sunday night for the last two years,” I said. “He’s the one who wanted me to have the paperwork. He was worried Diane would panic if something happened.”

“Good to know,” she murmured.

The elevator dinged on the third floor. The ICU doors slid open, and the smell of antiseptic hit me again, stronger here, mixed with something metallic and faintly sweet. Nurses at the station glanced up, straightened when they saw Patricia. One picked up a phone, probably calling someone to let them know the administrator was making rounds.

Diane was still standing guard at my father’s door, arms folded, face set. When she saw me step off the elevator beside Patricia, her skin went through three colors in as many seconds—white, then red, then a mottled purple.

“Mrs. Chen,” Patricia said, her voice calm but carrying down the entire corridor. Heads turned. Monitors beeped. “This man holds medical power of attorney for David Chen. He has full legal access to the patient and full authority over all medical decisions regarding his care.”

“That’s impossible,” Diane snapped. “I’m his wife. I’m his next of kin. This is absurd.”

“And he,” Patricia continued, gesturing to me, “is the legal health care decision‑maker, as designated by the patient in a notarized document filed with this hospital six months ago. Mr. Chen has every right to be here. In fact, in matters of medical decisions, he has more authority than you do.”

I watched the realization hit Diane like a wave. First disbelief, then anger, then something that looked uncomfortably like fear.

“You can’t do this,” she said, but her voice wobbled.

“Mrs. Chen,” Patricia said, her tone sharpening just enough to cut. “You just had the legal health care proxy removed from this facility by providing incomplete and misleading information to security. If you’d like to contest the power of attorney, you’re welcome to pursue legal channels. But as of this moment, hospital policy requires us to follow the directives of the designated agent. That’s Mr. Chen.”

Patricia stepped aside and turned to me.

“Mr. Chen,” she said. “Your father is waiting.”

I started toward the door. Diane’s hand shot out, her nails digging into my forearm hard enough to sting.

“You can’t do this to me,” she hissed, her voice low, all the icy composure gone. “I’ve been taking care of him. I’ve been here. You abandoned him two years ago for your precious career in Portland. You don’t get to swoop in now and act like the hero.”

I stopped. For once, I didn’t look away. I let her see everything—anger, grief, exhaustion, the one hundred and four Sunday calls sitting like weights in my chest.

“Actually, Diane,” I said quietly. “I can.”

Her grip tightened.

“You’re not family,” she said again, like repeating it might make it true.

“Family only,” I echoed. “Right?”

Her mouth opened and closed like a fish gasping for air.

I turned to Patricia without breaking eye contact with Diane.

“Can you clarify hospital policy on visitors when the medical power of attorney holder requests restricted access?” I asked.

“The health care proxy can restrict visitors as they see fit in the best interest of the patient,” Patricia said smoothly. “Including spouses. The proxy’s authority is absolute in medical decision‑making and patient welfare matters, within the bounds of the law and the patient’s directives.”

Diane’s face went crimson.

“David would never want this,” she said.

“David gave me this authority six months ago,” I replied. “He signed the papers, had them notarized, and filed them with this hospital. He knew exactly what he was doing. And right now, what he needs is calm, not drama.”

I pulled my arm free.

“I’d like privacy with my father, please,” I told Patricia. “No visitors except medical staff until I say otherwise.”

“Of course, Mr. Chen,” she said. She pulled out her phone and tapped quickly. “I’m noting that in his file. Security restriction placed at the request of the health care proxy.”

She turned to the two guards who’d appeared at the end of the hallway—different faces this time, same navy uniforms.

“Mrs. Chen is to leave the ICU wing immediately,” she said. “She’s not to access Room 347 or patient David Chen without Mr. Chen’s explicit authorization. If she attempts to reenter in violation of that directive, she’s to be removed from the premises.”

“You’ll regret this,” Diane spat, tears finally spilling over, streaking her makeup. “When he wakes up—if he wakes up—you’ll pay for this. I’ll make sure everyone knows what you did. Your Uncle Tom, your Aunt Linda, everyone at church, everyone he works with. They’ll all know you kept his wife away from him while he was…”

She couldn’t bring herself to finish the sentence.

“If he wakes up,” I said quietly, “I’ll ask him what he wants. Until then, I’m doing exactly what he trusted me to do. The way he put it in writing.”

The guards took her gently by the arms. Not rough, not cruel, just firm. She twisted once, twice, then let herself be led away, still throwing accusations over her shoulder. Threats about lawyers. Statements about how I’d always been ungrateful. Promises that she’d “fix this” and “set the record straight.”

The elevator doors closed on her voice at the far end of the hall. The sudden silence felt heavy.

Patricia touched my shoulder lightly.

“I’m sorry it came to that, Mr. Chen,” she said. “Dr. Sarah Winters is your father’s cardiologist. She’s excellent—twenty years of cardiac ICU experience. I’ll let her know you’re here and that you’re the decision maker.”

“Thank you,” I said.

“And Mr. Chen,” she added, lowering her voice. “I’m also documenting this incident in our security records. If Mrs. Chen attempts to interfere again or provides false information to staff, we’ll take further action. Patient welfare includes protecting health care proxies from harassment. You shouldn’t have had to fight your way in here.”

She walked away toward the nurses’ station, already talking quietly with the charge nurse. Heads bent. Notes taken. Systems shifting.

For the first time since I’d gotten the call, it felt like something—anything—was under control.

I turned to the door of Room 347 and pushed it open.

Up close, my father looked even worse.

The machines I’d glimpsed from the hall loomed larger now. The cardiac monitor traced green lines across a black screen, sharp peaks and valleys measuring electrical whispers inside his chest. An IV pole held clear bags of medication dripping into his veins, each labeled with names I couldn’t pronounce. A ventilator hissed and clicked in the corner, pushing air into his lungs in precise mechanical bursts. Hiss. Click. Hiss. Click. The sound was steady and unnatural, like a metronome someone had set to “barely alive.”

Dad’s face was slack, skin a shade too close to the pillowcase. The strong jaw that had shouted encouragement from soccer sidelines now looked fragile. His hair—more gray than black these days—lay plastered to his forehead with hospital sweat. Age had crept up on him slowly over the years; this looked like it had mugged him in a parking lot.

I pulled the visitor chair close and sat, fingers suddenly clumsy as I reached for his hand. It felt cool and papery, the way old book pages feel when you turn them slowly.

“Hey, Dad,” I said softly. “It’s Marcus. I’m here.”

The monitors beeped. The ventilator hissed. He didn’t move.

“Sorry it took me eight hours,” I added, because we’d always filled silence with bad jokes. “Traffic near Boise was a nightmare. You know how construction gets near the state line.”

Nothing. But I hadn’t really expected anything.

For a while, all I could do was sit there and watch numbers change on screens. Heart rate: 58. Blood pressure: 110 over 65. Oxygen saturation: 95%. Were those good? Bad? Acceptable? The numbers might as well have been lottery tickets for all I understood them.

A soft knock sounded against the doorframe. I looked up.

A nurse stood there, early twenties maybe, dark hair pulled into a messy bun, purple scrubs covered in cartoon stethoscopes. Her badge read ALICIA RODRIGUEZ, RN.

“You must be Marcus,” she said, voice gentle.

“Yes,” I said, releasing Dad’s hand long enough to stand. “You’re the one who called me this morning?”

She nodded. “I’m the one who found his emergency contact form when he came into the ER. He had you listed as primary.”

“Thank you,” I said, throat tight. “For calling. For… all of this.”

“You don’t have to thank me,” she said, moving around the bed with practiced efficiency, checking IV lines, straightening tubing. “Your father talked about you a lot before the heart attack.”

“He did?”

She smiled faintly. “Showed me pictures on his phone. Portland, the mountains, your apartment with the view of Mount Hood. He said you were working on some kind of water project?”

“Environmental monitoring systems,” I said automatically. “Sensors in rivers so we can track pollution in real time.”

“Right,” she said. “He was very proud of that. Said you were the smartest thing he’d ever done. That you got your mom’s brains and his stubborn streak, which made you unstoppable.”

My throat closed. For a second I couldn’t speak.

“He really said that?” I managed.

“More than once,” she said. “Look, I know there was… drama earlier. We all heard Diane at the nurses’ station. But in the time I’ve known your dad, he never sounded abandoned. He sounded proud. And happy when you called.”

I nodded, blinking hard.

“Dr. Winters will be in soon,” Alicia said, making a note on her tablet. “She’ll explain everything better than I can. His condition, the plan, what we’re watching for. It’s serious, Marcus. I won’t lie to you. But he’s stable for now. That’s something.”

“Stable,” I repeated. The word felt like a thin board stretched over a deep canyon. Better than nothing. Still terrifying.

“If you need anything,” she added, “coffee, water, someone to translate medical jargon, hit that call button. We’re here.”

After she left, the room felt bigger and smaller at the same time. Bigger because there was nothing to distract me from the machines and the pale hand in mine. Smaller because everything outside the four walls suddenly seemed irrelevant.

I stayed like that for what could have been twenty minutes or two hours, talking to him in a low voice about nothing and everything. I told him about the project I’d just landed at work—a watershed monitoring contract for an entire county, budget just shy of $750,000, the kind of number that would have made him whistle. I described the view from my apartment: Mount Hood in the distance, the Willamette River when the light hit it just right. The coffee shop downstairs that roasted their own beans and played Sinatra on Sunday mornings.

I told him about the chipped white mug in my car—the one with the faded American flag—that I’d grabbed without thinking on my way out the door, because it felt wrong to drive to him without it.

At some point the steady whoosh of the ventilator and the quiet beeps of the monitors lulled me into a sort of exhausted trance. That was how Dr. Sarah Winters found me.

“Mr. Chen?”

I jerked awake, my neck protesting the angle I’d let it rest in. A woman in her early forties stood by the bed, white coat over dark blue scrubs, stethoscope looped around her neck. Her dark hair was shot through with just enough gray to suggest experience, pulled back in a practical ponytail. Her badge read SARAH WINTERS, MD – CARDIOLOGY.

“I’m Dr. Winters,” she said, extending a hand. “Cardiac intensive care. I’m overseeing your father’s treatment.”

“Marcus,” I said, standing to shake it. Her grip was firm, her eyes clear and direct.

“I understand you’re David’s health care proxy,” she said. “He filed the paperwork with us in April.”

“Yes,” I said. “He designated me about six months ago.”

“Good,” she said. “That makes this conversation easier. We can talk frankly without worrying about HIPAA restrictions.”

She pulled up Dad’s chart on the computer mounted to the wall, scrolling through labs and notes.

“Your father suffered an acute myocardial infarction this morning,” she said. “A heart attack. At approximately 5:30 a.m., your stepmother called 911. Paramedics arrived within seven minutes, which likely saved his life. He had a complete blockage of the left anterior descending artery—we sometimes call it the ‘widowmaker’ because it’s often fatal.”

The word stuck in my brain like a thorn.

“We performed an emergency cardiac catheterization,” she continued, bringing up an image of what looked like a ghosted outline of a heart’s blood vessels. “We placed two stents to open the blockage, but there was significant damage to the left ventricle before we could restore blood flow.”

“What does that mean?” I asked. My voice sounded calmer than I felt.

“It means his heart isn’t pumping as efficiently as it should,” she said. “We’re using medications to support his blood pressure and heart function. He’s on a ventilator to reduce the workload on his heart while it begins to heal.”

“Is he going to make it?” I asked, the question I’d been trying not to phrase so bluntly.

Dr. Winters met my eyes. She didn’t look away, didn’t soften the gaze with false comfort.

“The next forty‑eight hours are critical,” she said. “If he remains stable—no additional cardiac events, no major complications—his chances improve significantly. But I need to be honest with you, Marcus. The damage was extensive. Even if he survives this initial crisis, he’ll need cardiac rehabilitation, significant lifestyle changes, and possibly further interventions down the line.”

“But he could survive,” I said.

“Yes,” she said. “He could survive. He’s relatively young, sixty‑three, and aside from this event, his labs suggest he took reasonably good care of himself. He’s fighting. The numbers on these monitors show that.”

I let out a breath I didn’t know I’d been holding.

“Now,” she said, her voice gentler, “we need to talk about his wishes regarding aggressive interventions and end‑of‑life care. It’s standard for ICU patients in critical condition. I see he has an advanced directive on file.”

“Yes,” I said quickly. “It should be attached to the medical power of attorney paperwork.”

She scrolled again.

“Here it is,” she said. “He’s very clear. No prolonged life support if there’s no reasonable chance of meaningful recovery. No extraordinary measures if brain function is severely compromised. But we’re not there right now. Everything we’re doing at this stage is standard post‑heart‑attack care with a reasonable chance of helping.”

“I understand,” I said, even though part of me wanted to plug my ears and hum.

“Do you have any questions for me?” she asked.

I had a thousand. I picked the one that mattered most in that moment.

“Can he hear me?”

“Maybe,” she said. “Probably not consciously—he’s sedated to keep him comfortable and prevent agitation—but some research suggests patients retain some awareness under sedation. It doesn’t hurt to talk to him. Many patients report later that they remember voices, or the feeling that someone was there.”

“So I should keep talking,” I said.

“It won’t hurt,” she said. “And it might help both of you.”

After she left, I pulled the visitor chair even closer and resumed my one‑sided conversation. I told him stories he already knew, because telling them made me feel like I was anchoring him to this side of things. The time he’d run alongside my bike in the cul‑de‑sac, refusing to let go of the seat until I screamed at him to. The way he’d sat through every middle school soccer game, even the ones in freezing rain, wrapped in a blanket patterned with little US flags that Mom bought on clearance one July.

I told him the thing I’d never said out loud:

“I know you picked me over Diane for the power of attorney,” I whispered. “I’m not going to mess that up. I promise.”

That was my wager with the universe: if he trusted me enough to put my name on that line, I would do whatever it took to honor it.

Somewhere around midnight, the vents’ soft rush and the rhythmic beeping of monitors blurred into a white noise that pulled at my eyelids. I dozed off in the chair, head tilted back, mouth dry.

Raised voices in the hallway jolted me awake.

“I don’t care what he said,” Diane’s voice cut through the wall, sharp and frayed at the edges. “I’m going in there.”

“Ma’am, you’re not on the approved visitor list,” a new security guard said. A woman’s voice this time, thicker with authority. “You’ve been restricted by the health care proxy.”

“I’m his wife,” Diane insisted. “You can’t keep me away from my husband.”

I stood, joints protesting, and went to the doorway. When I opened it, the scene in the corridor hit me like stage lights.

Diane stood at the nurses’ station, makeup smeared, hair frizzed from hours of stress. Beside her were my uncle Tom and his wife, Linda. Tom’s accountant‑calm looked frayed; Linda’s eyes flashed.

“Marcus,” Tom said when he saw me. “What the hell is going on? Diane says you banned her from seeing David.”

“I haven’t ‘banned’ anyone,” I said carefully, aware of Alicia’s eyes on us from behind the desk and the security sergeant standing between Diane and the ICU doors. “I’ve restricted visitors to what’s best for Dad while he’s critical. That’s what Dr. Winters recommended. Too much stress isn’t good for him.”

“She’s his wife,” Linda cut in. “That’s immediate family. She has a right to be here.”

“And I’m his son and his health care proxy,” I said. “Dad gave me that responsibility six months ago because he wanted someone who would listen to the doctors and follow his wishes. That’s what I’m doing.”

Tom rubbed his temples. “Marcus, this seems extreme. Diane’s been taking care of him. She was the one who called 911. She’s scared.”

“She had me forcibly removed by security this afternoon,” I said flatly. “Told them I wasn’t family. Said Dad didn’t want to see me.”

Linda’s gaze snapped to Diane. “Is that true?”

“It was a misunderstanding,” Diane said quickly, color rising in her cheeks. “I was upset. David had just been taken in. I wasn’t thinking clearly.”

“You told security I was harassing you,” I said. “You watched them drag me to the elevator and smiled. That’s not a misunderstanding.”

Tom looked between us, his peacekeeper instincts warring with the facts.

“Can we at least see him?” Linda asked, voice softer now. “Tom is his brother. He has a right.”

I glanced toward the room where Dad lay. He was stable, Dr. Winters had said. Stable, but not out of danger. Stress wasn’t good. But Tom had always been good to Dad. And Linda had texted me instead of taking Diane’s story at face value.

“Five minutes,” I said finally. “One at a time. Alicia will stay in the room. No drama. No raised voices. If anyone upsets him, it’s over.”

Tom went first. When he came out, his eyes were red, his shoulders sagging.

“He looks bad, Marcus,” he said quietly. “Really bad.”

“I know,” I said.

Linda went in next. She came out pale and silent, squeezing Tom’s hand hard enough to whiten her knuckles.

Diane moved toward the door.

“Not tonight,” I said, stepping into the doorway.

“You can’t do this,” she said, eyes wide with fury and something like panic.

“Yes,” I said, too tired to sugarcoat it. “I can. That’s literally what medical power of attorney means. Dad asked me to make hard decisions when he couldn’t. Right now, that means controlling stress. You and I both know you’re not going to walk in there and sit quietly for five minutes.”

She opened her mouth to argue.

Tom put a hand on her arm. “Come on, Diane,” he said. “Let’s go home. Let Marcus do what David asked him to do.”

She yanked her arm free but didn’t push past me. For once, she seemed to understand that the guard watching us—from the way her hand rested on her radio and the way Alicia’s fingers hovered near the phone—meant this wasn’t a fight she could win tonight.

They left. Diane looked back once, her face twisted with anger and something else. Fear again, maybe. Not just of losing Dad, but of losing control of the story she’d been telling about us for years.

The next two days were the longest of my life.

I barely left the ICU. I slept in the chair when exhaustion dragged me down, waking with a stiff neck and pins‑and‑needles in my legs. Alicia and the other nurses brought me coffee in flimsy paper cups, crackers, sandwiches from the cafeteria that tasted like cardboard but kept me conscious. Every time a monitor beeped differently, my heart leapt into my throat.

I watched other families move through their own emergencies. Parents in sweatshirts clutching stuffed animals, grandparents in baseball caps, a teenager in a letterman jacket staring blankly at the wall. Every story in that hallway revolved around the same ugly truth: someone they loved was lying behind a door, hooked to machines, and there were no guarantees.

But unlike most of them, I had an extra layer of drama: the social fallout of being the son who’d “abandoned” his father and then come back wielding legal paperwork.

I heard snippets at the coffee station.

“Diane is beside herself,” one of Dad’s church friends whispered to another. “She says Marcus threw her out.”

“She also said he never visits,” the other replied. “But Alicia told me he talks about those Sunday calls all the time.”

Little by little, the story Diane had written started to fray at the edges.

On the third morning, Alicia poked her head into Dad’s room.

“Your stepmother is in the waiting room with some folks from your dad’s church,” she said. “They’re asking to see him. Pastor Michael is there.”

Pastor Michael had officiated my parents’ wedding and my mother’s funeral. He’d baptized me in a small brick church with faded red carpet and a US flag standing next to the pulpit. The man had been a fixture in our lives for as long as I could remember.

I splashed water on my face in the tiny sink in the corner of the room, ran fingers through my hair, and followed Alicia to the waiting room.

It was packed. Diane sat in one corner, eyes puffy, clutching a tissue. Beside her were the Yamadas, the Hendersons, an elderly couple whose names I’d forgotten but whose casseroles I remembered from when Mom died. Pastor Michael stood when he saw me, his gray beard neatly trimmed, his eyes kind but creased with worry.

“Marcus,” he said, taking my hand. “We heard about David. We wanted to come pray with him.”

“He’s stable,” I said. “Sedated. On a ventilator still. He’s not really responsive.”

“Then we’ll pray quietly,” Mrs. Henderson said. “Just sit with him. Let him know he’s loved.”

I looked at their faces. These were good people. People who’d shown up when Dad needed them. People who weren’t part of the tug‑of‑war between Diane and me, except in the way she tried to recruit them.

“Okay,” I said. “But we have to keep things calm. Two at a time. Five minutes each. No touching except for holding his hand. No crying on his chest, no dramatics. The nurses will be watching.”

They nodded, accepting the rules without argument.

Pastor Michael went in first with Mr. Yamada. They came out ten minutes later, eyes damp, hands clasped.

“He looks rough,” Pastor Michael said softly. “But he’s still David. I could feel it.”

People went in and out for the next hour. Quiet prayers. Silent tears. No one tried to break my rules.

Diane waited until the end.

“Please,” she said when everyone else had taken their turn. “Five minutes. That’s all I’m asking.”

Her voice didn’t have the sharpness I was used to. It sounded small. Frayed.

I studied her. Her makeup was ruined. Her hair, usually perfectly styled, hung limp. She looked less like the polished woman from Facebook photos and more like a human being who’d slept in a hospital chair for two nights.

“Five minutes,” I said. “Alicia stays inside the whole time. If you start anything, if you upset him, it’s over.”

She nodded, swallowed hard, and went in.

From the window in the hallway, I could see just enough. She took his hand. She cried—real tears this time, not the theatrical ones she’d used at family gatherings—but she kept her voice low. She leaned in and said something in his ear I couldn’t hear. For once, it didn’t look like a performance.

When she came out, her face was blotchy, her eyes swollen.

“Thank you,” she said quietly.

“He’s your husband,” I said. “I’m not trying to keep you away forever. I’m just trying to protect him while he can’t protect himself.”

She nodded once, then walked back to the waiting room without another word.

Dad woke up two days after the heart attack.

That morning, Dr. Winters told me she was going to start easing off the sedation, see how he responded. “His vitals are stable enough to try,” she said. “We’ll go slowly.”

I sat by his bed, heart banging against my ribs harder than it had when the guards escorted me out of the ICU.

Around two in the afternoon, his eyelids fluttered. Once, twice. Then they opened.

For a moment his gaze was unfocused, drifting over the ceiling tiles, the light fixture, the corner of the room where the ventilator hummed. Then his eyes found me.

“Dad,” I said, leaning forward, taking his hand. “Hey. It’s Marcus. You’re in the hospital. You had a heart attack, but you’re okay. You’re going to be okay.”

The breathing tube still down his throat prevented him from speaking. He squeezed my hand instead, weak but intentional.

Dr. Winters appeared almost instantly, as if she’d been watching the monitors at the nurses’ station.

“David,” she said, bending over him. “I’m Dr. Winters. Can you squeeze my hand?”

He did, a small clench around her fingers.

“Good,” she said. “Can you wiggle your toes for me?”

Beneath the blanket, his feet shifted.

“Excellent,” she said. “Do you know where you are?”

He nodded a fraction of an inch.

“You had a heart attack,” she explained. “We placed stents in your heart. You’re in the ICU recovering. You’re doing well enough that we’re going to take this breathing tube out this afternoon if you keep improving. Do you understand?”

Another tiny nod.

“Do you know who this is?” she asked, gesturing toward me.

Dad’s eyes moved to mine again. He squeezed my hand harder.

“Your son has been here the entire time,” Dr. Winters said. “He’s your health care proxy. He’s been making your medical decisions. You chose very well.”

Something like a smile tugged at the corners of his mouth around the tube.

They removed the ventilator later that afternoon. It wasn’t pretty. There was coughing, gagging, a whole lot of suctioning and medical phrases I didn’t understand. But eventually the tube was gone and Dad was breathing on his own, oxygen delivered through a nasal cannula instead.

His first words, voice raspy and weak: “Marcus…you came?”

“Of course I came,” I said, my own voice breaking. “Did you really think I wouldn’t?”

“Eight hours?” he whispered.

“Worth every mile,” I said.

His eyes drifted closed, then opened again.

“Diane?” he asked.

I hesitated.

“We’ve worked it out,” I said. It wasn’t entirely true, but it also wasn’t entirely false. “She’s been here. Your whole church has. Everyone’s worried about you.”

He let out a breath that was almost a laugh and winced.

“Bet she’s mad…about POA,” he said.

“I think ‘mad’ is putting it mildly,” I said.

“Good,” he whispered.

I blinked. “Good?”

“Told her…months ago,” he said, each word an effort. “She thought…paperwork didn’t matter. That she could…talk doctors into anything. Needed someone who’d…listen. Follow directions. You.”

I swallowed past the lump in my throat.

“You scared me,” I said.

He closed his eyes again, exhaustion dragging at his features.

“Scared…myself,” he murmured. “Thank you…for coming. For staying. For being…” He coughed, winced. “For being exactly…who I needed you to be.”

He drifted off again, his hand still in mine.

Three days later, they moved him from the ICU to the cardiac step‑down unit. Less equipment, more natural light. The room had a window that looked out over a small courtyard with a couple of struggling trees and a picnic table no one ever used.

I called my boss in Portland from the hallway.

“Take whatever time you need,” she said. “Family first. We’ll redistribute your tickets. HR will mark it as emergency leave. Don’t check your email unless you’re bored and can’t sleep.”

“Thanks, Sarah,” I said, relief loosening a knot I hadn’t realized was there. “The contract—”

“Will still be there,” she cut in. “Water doesn’t stop needing monitoring because your dad had a heart attack. We’ll pick it up when you’re ready.”

In the step‑down unit, Diane and I developed an uneasy truce.

She visited in the mornings; I took afternoons and evenings. Sometimes we overlapped, hovering on opposite sides of the bed, each talking to Dad about neutral topics—the weather, the Mariners, the blandness of hospital food. When conversations threatened to veer into anything sharper, one of us found an excuse to step out.

One afternoon, about a week after the heart attack, I came back from a coffee run to find Diane waiting for me in the hallway.

“I owe you a real apology,” she said, before I could say anything.

I blinked. The words sounded weird in her mouth, like a foreign language.

“Not just for the hospital,” she continued. “For the last two years. I made it hard for you to be part of this family. I felt threatened by your relationship with David. That was wrong.”

I leaned against the wall, the cool paint grounding me.

“Yeah,” I said. “It was.”

“I don’t expect us to be friends,” she said. “But maybe we can be…civil. For David’s sake.”

I thought about one hundred and four Sunday calls. About the security guards’ hands on my arms. About her voice saying you’re not his real son.

“I can do civil,” I said finally.

She nodded, some of the tension leaving her shoulders.

“And Marcus?” she added, glancing through the window where Dad was dozing in his reclined bed, a blanket with little US flags someone from church had dropped off tucked around his legs. “Thank you for making the medical decisions. I would have panicked. David was right to trust you.”

It wasn’t forgiveness. Not yet. Maybe not ever, not fully. But it was a crack in the wall between us.

When Dad was strong enough to sit up without getting dizzy, I brought the chipped white mug in from my car. The faded American flag on the side looked especially worn under the fluorescent lights.

“You brought it,” he said, smiling weakly when he saw it.

“Couldn’t do this without it,” I said, setting it carefully on the tray table where he could see it. “Figured if we can’t have Sunday calls, we can at least have the mug.”

He rested his hand on it for a second, fingers tracing the outline of the flag.

“One hundred and four Sundays,” he said quietly.

“You kept count?” I asked.

“Of course I did,” he said. “Every week I’d tell Diane, ‘Marcus is calling tonight.’ She’d roll her eyes. Said you were showing off. I said you were showing up. There’s a difference.”

He looked at me, eyes clear.

“That’s what family does,” he said. “Shows up.”

Weeks later, after rehab sessions and medication adjustments and endless follow‑up appointments, I drove him home from the hospital. The mug came with us, riding in the cup holder between us like a small, ceramic witness.

Diane met us at the door, the tension between us muted now, reshaped by what we’d been through. She fussed over his medications, his follow‑up schedule, the sodium content of every food in the pantry. I carried in bags, set up the recliner he’d sleep in for a while, made a pot of decaf in his ancient drip coffeemaker.

Before I left to drive back to Portland, he pressed the chipped white mug into my hands.

“You keep it,” he said.

“Dad, it’s yours,” I protested.

“It was ours,” he corrected. “Now it’s yours. Take it back to Portland. Put it on your kitchen table. When I call you on Sunday nights, we’ll both know it’s there.”

My throat tightened.

“Okay,” I said. “Deal.”

The next Sunday night, I sat at my table in Portland, the chipped mug in front of me, empty but present. Outside my window, an American flag flapped lazily on a neighbor’s balcony, catching the last light of the day. My phone rang right on time.

“Hey, old man,” I said, answering.

“Hey, kid,” he said. “How’s the river data?”

We talked about his rehab, about my project, about the weather and the Mariners and nothing at all. Ordinary things. Quiet things.

“Remember when Diane told me ‘family only’?” I said at one point, half‑joking.

He snorted softly.

“Yeah,” he said. “She was wrong.”

“What does ‘family only’ mean to you?” I asked.

“It means the people who keep showing up,” he said. “Paperwork or not. Blood or not. The ones who drive eight hours on bad coffee; the ones who answer the phone one hundred and four Sundays in a row.”

I looked at the chipped mug, at the tiny faded flag on its side.

“Good,” I said. “We’re on the same page.”

We didn’t talk about the hospital much after that. Not the guards, not the hallway showdowns, not the way everything almost went the other way. We didn’t need to.

Every Sunday night, when the phone rang and I wrapped my hands around that chipped white mug, I remembered.

I remembered the night my stepmother tried to lock me out of my father’s room.

I remembered the one phone call that flipped everything.

And I remembered the quiet miracle that, for once, the story about who counted as “family” ended the way it should have all along.

News

My father-in-law cut me out of family photos at our daughter’s first birthday. “Real family only,” he said. My wife didn’t defend me. I left the party early. By the time they needed me to co-sign their mortgage refinance, I was already filing for divorce.

My name echoed through the university arena, sharp against the floodlights, as I walked across that stage expecting—hoping—to see them….

My father-in-law cut me out of family photos at our daughter’s first birthday. “Real family only,” he said. My wife didn’t defend me. I left the party early. By the time they needed me to co-sign their mortgage refinance, I was already filing for divorce.

My name echoed through the university arena, sharp against the floodlights, as I walked across that stage expecting—hoping—to see them….

My father-in-law cut me out of family photos at our daughter’s first birthday. “Real family only,” he said. My wife didn’t defend me. I left the party early. By the time they needed me to co-sign their mortgage refinance, I was already filing for divorce.

My name echoed through the university arena, sharp against the floodlights, as I walked across that stage expecting—hoping—to see them….

I refused to go on the family vacation because my sister brazenly brought her new boyfriend along – my ex-husband who used to abuse me; “If you’re not going, then give the ticket to Mark!” she sneered, and our parents backed her up… that night I quietly did one thing, and the next morning the whole family went pale.

The night my mother’s number lit up my phone for the twenty-ninth time, I was sitting on my tiny city…

my husband laughed as he threw me out of our mansion. “thanks for the $3 million inheritance, darling. i needed it to build my startup. now get out – my new girlfriend needs space.” i smiled and left quietly. he had no idea that before he emptied my account, i had already…

By the time my husband told me to get out, the ice in his whiskey had melted into a lazy…

My father suspended me until I apologized to my sister. I just said, “All right.” The next morning, she smirked until she saw my empty desk and resignation letter. The company lawyer ran in pale. Tell me you didn’t post it. My father’s smile died on the spot.

My father’s smile died the second he saw my empty desk. It was a Thursday morning in late September, the…

End of content

No more pages to load